I was born an insider, but I pretty much lived as an outsider-Abhay Deol

8:53 AM

Posted by Fenil Seta

Abhay Deol with mid-day’s entertainment editor Mayank Shekhar at the latest edition of Sit with Hitlist. Pics/Shadab Khan

Decoding the rise & fall of Mumbai film industry’s ultimate insider-outsider!

Mayank Shekhar (MID-DAY; January 21, 2023)

Shortly after our conversation, before a live audience, Abhay Deol is scheduled to meet Shekhar Krishnamoorthy, the person he plays in the Netflix series, Trial By Fire — based on the life of a middle-class Delhi couple, who fought the city’s top real-estate developers, post the death of both their children, in the 1997 Uphaar Cinema fire tragedy.

Which is also when we realize Deol had chosen to consciously stay away from the real-life inspiration for his part, during the process of making the series. Deol is Punjabi by ancestry, unlike Krishnamoorthy, with the most Tamil surname. In fact, Deol has played a Tamilian before this.

That was as the bureaucrat Krishnan, for Dibakar Banerjee’s Shanghai (2012). In an episode dedicated to Deol’s films, on a podcast named Khabardaar, that I was listening to before meeting the actor, the hosts — shout-out to wonderful ladies, Aparita Bhandari, Baisakhi Roy—make an observation on Deol’s walk onscreen. They believe it is the same in all his films. Except, Shanghai, if you notice the minutiae.

Firstly does he agree, and was that consciously so, I ask Deol: “There are physical characteristics that I suppose you don’t change easily. You’re unaware of them. With Shanghai, that may be true. Not that I consciously worked on my walk, though. I did have to work on my accent. Krishnan is a Tamil Brahmin.”

“And I had to put on a Hindi, like a Tamilian would speak it, which is hard to find. Because no Tamilian really speaks Hindi — they speak to you in English. Also, we don’t have an infrastructure of accent training for actors in our country. So we found this out-of-work Tamilian writer, who I worked with, and developed a system [for it].”

If we must get deeper into this accent thing still, for instance, Deol recalls, “I hope I haven’t mixed up my memory, but I was really working on the phonetics — there is no ‘ha’ sound in Tamil, and there is no ‘ba’. In Tamil, you could pronounce my name closer to ‘Apaay’. Stuff like that was insightful. This is besides mimicking my accent-trainer off-camera — so I would know how he might say my dialogues.”

The ladies of Khabardaar podcast might wanna notice this the next time they watch Shanghai. Krsihnamoorthy in Trial By Fire, Deol points out, is different from Krishnan, because he’s a Tamilian, but essentially from Delhi.

He has what one could call a more neutrally North Indian or ‘Delhi’. Which is also a character Deol has played in Oye Lucky Lucky Oye (OLLO) — another real-life person he obviously didn’t meet, before playing him on screen. Bunty Chor was the local swindler, where would you find him?

OLLO (2008) tragically released in theatres, when the “the firings were still on” during 26/11 terror attacks in Mumbai. My favourite memory of OLLO is an off-screen one from the film’s BTS video online, where a dog is after Bunty Chor (Deol), who’s jumping off a tall building-gate. Banerjee asks him to turn around for the camera, so the audience knows the lead actor performed this himself, instead of a body-double.

Deol says, “It’s fun doing stunts, as much as I can. I think Dibakar was a bit surprised about how easily I was scaling such a large gate, and he said he wanted people to see it!”

Sticking to Delhi, and characters inspired by actual events/people still, how about Anurag Kashyap’s Dev D (2009). I learnt this much after watching the film that the role was in fact somewhat based on Deol’s own life. Meaning, obsession in love, and indeed experiments with drugs. If true, kindly elaborate?

“Well, I wanted to contemporize the (Sarat Chandra Chatterjee) book, because I felt there was something wrong there — with such a male, patriarchal view of a man-woman relationship, where women are falling over Devdas. No matter what he does, he can never be wrong. I grew up in an environment, where drugs and alcohol were all available.”

“My Chanda (Kalki’s) character was far stronger than what eventually got made into the movie. She was an East European pole-dancing escort, who is fine the way she is — making great money, traveling the world. She takes pity on him (Dev). Obviously it worked for Anurag [that] she was as vulnerable as he [Dev], and she was a victim too. For me, he was the only victim. The women only grew stronger from there.”

Did he know the Polish escort? “I am not going to tell you! I know all sorts of people; let’s just put it that way. Yeah, I know a few escorts ‘n’ all.”

Let’s pause at the movie titles here: Banerjee’s Shanghai, OLLO. Kashyap’s Dev D. Also from a time when both Kashyap and Banerjee were the ‘new-age filmmakers’, early on in their directorial careers. I wonder what Deol thinks of the trajectory they took thereafter.

Frankly, he doesn’t have much to say, besides “conforming to commercial pressure” that becomes inevitable in some cases. He could sense the “creative genius of Banerjee in LSD (2010)”. As for Kashyap, I find it surprising that he hasn’t seen any of his films since Dev D! Not even Gangs Of Wasseypur (2012)? What; did they have a fallout or something, I ask.

“Well, [Kashyap] went in public, and said a lot of lies about me.”

For example? “One lie was that I demanded a [five-star] hotel room [during the shoot of Dev D]. He had actually come up to me and said, ‘Listen you can’t stay with us, you are a Deol. So, I want to put you up in a hotel room.’ He literally told me that. What he told the press was that I demanded it.” The reference here is to Deol’s profile published in Huffington Post (June 5, 2020).

He continues, “So, there was clearly a lot going on at the time, which was not professional. I had my heart on my sleeve, and all that is great — but you get taken advantage of, and then you get reactive. So, he [Kashyap] was a good lesson for me. Then I just avoided him, because I don’t need toxic people in my life. Life is too short, and there is so much more to explore. But he (Kashyap) is definitely a liar, and a toxic person. And I would warn people [about] him.”

This outburst is evidently in response to Kashyap’s quote about Deol in the Huffington Post report. Deol adds later, “I don’t look in the past. When Anurag said that crap about me in public, he sent me ‘apology’ messages.”

“He does that all the time. He was like, ‘You want to shout at me, scream at me…’ And I was like, ‘I don’t care. It’s been 12 years. You don’t feature in my thoughts even now; get over it.’ He said, ‘Forgive me, because I have had a bad day.’”

“I said you are forgiven. I never had a personal agenda. It was far bigger than just me. That is how I feel about everything. How much of this is he going to do? And I would have never taken his name and said the things, had he not gone public [either].”

Raking this up is important only because lead actors, or stars, have always been the medium to tell stories on screen — even if in the off-stream space, so to say. And by the mid Noughties, Deol was at the centre, if not the pioneer, of a movement of sorts, within Bollywood—picking up young, untested directors to star in their scripts/films, on a leap of faith, first.

“The first five movies of mine were all by first-time directors,” he recalls. Let’s pause again to name these debutants: Imtiaz Ali (Socha Na Tha), Shivam Nair (Ahista Ahista), Reema Kagti (Honeymoon Travels Pvt Ltd), Sanjay Khanduri (Ek Chaalis Ki Last Local), Navdeep Singh (Manorama Six Feet Under).

These are also films that got defined as Hindi commercial cinema, merging with an entertaining art-house — ‘H-indies,’ if you like. At least a couple of the directors did fairly well for themselves — after that firm footing in the film industry.

I can see why it’s got Deol a li’l pissed off now that I want him to dwell on what he thinks of their careers as well — he did like Ali’s Jab We Met, more than Rockstar, which in turn was still outside Ali’s usual “love-triangle zone”, and therefore a step-up: “Why am I commenting on all this — [is that] what the show/conversation is about?” Of course not.

I guess what we’re getting at is an oft repeated jibe that a lot of these directors — take Ali, for example, who got his debut due to Deol — never worked with him thereafter. Is that a fair observation, with anything deeper to it?

“And Anurag used to say, this is why directors [don’t work with me]… I know a lot of actors don’t want to work with him. But I see what you mean. Or where you are coming from. I did sense this feeling [later towards me]: ‘You know, you are not big enough!’”

“Which is ironic, because when I worked with them, neither were they! You either believe in someone, or a vision — even if it goes against the norm. Or you can say, I will keep my vision, but I will acquire bigger powers [to execute it]. Because I will get more money, I suppose. Also, I was taking a lot of it on myself, and I know I made mistakes. I am searching for answers to give you, and I hate making it about me, when it’s about somebody else.”

Consider the career graph. In terms of box-office plus cult-grade, Zoya Akhtar’s multi-starrer Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara (2011) is possibly Deol’s high point. A string of seriously superb films right before, and after. And then there is s sharp slump 2013 onwards, almost a freefall.

He’s had a release almost every year. So he’s very much been around since. The films/series are, again, by mostly first-time directors, or fresh talents, at any rate; experimental in their own right.

You can have your views on, say, One By Two (2014), Happy Bhaag Jayegi (2016), Nanu Ki Jaanu (2018), Chopsticks (2019), What Are The Odds (2019)… Good or bad is a subjective take anyway. But you know, none of them are really, well, did he lose his mojo, how do I put it….

“It’s just a fact. You don’t have to justify [your question],” Deol comes to my rescue. As for the kind of work that comes your way, he says, “Everything is [a] collective [call]. And I don’t like talking about it, because I don’t want to come across sounding bitter, or a victim. I don’t care. But when you take a stand, then you take a stand. And that has consequences. Are you ready to face those consequences?”

Exactly what stand, for example, could do someone in? “I don’t know. Calling out people for endorsing fairness creams?” Would that mean those who endorse fairness creams would debar you right away?

“It is not as simple as that. I did a guest appearance in Shah Rukh’s Zero, and he is a really dignified man. But there is a collective [thing that happens]. Say, showing up with a black eye on a red carpet, and calling out Bhushan Kumar by name, and saying T-Series blah, blah. Or constantly saying, why do we only have song and dance [in our films]…”

Deol has been equally vocal, in public, about critiquing his own films, with misplaced intentions — whether that be Aisha (2010), or Raanjhanaa (2013). Surely that’s hardly mastering the art of winning friends and influencing people. But you can tell—frankly, he doesn’t give a damn. And that’s what makes him more fun than the current crop of polite suckers for boring heroes.

Also some of his criticisms could emanate from ideas he wished to champion, but found no takers, around that time. Navdeep Singh’s Basra famously got shelved. As did a zombie comedy called Rock The Shaadi, after shoot. I fish out an old video of him consulting a tarot card reader, in Simi Garewal’s TV show — to check if one of his dream projects would come true.

Deol remembers it was an international film, with debutant filmmakers from abroad, who nobody wanted to put money on. They still haven’t made the film, and he had to stop trying eventually.

“So yeah, post 2013, it was tough. I also took a backseat. Now I don’t want to go back and pretend like nothing ever happened, or be a different person — so, I am going to sit back, and see what comes my way. And quietly work. If that works, it works. If it doesn’t, so be it!”

As for the so-called song and dance, Deol says it’s not like he has an issue with the genre: “At least three ideas of mine are full of songs. One of them was Dev D (18 numbers in the soundtrack).”

The film was a major winner at the box-office, for its budget. Deol remembers, “Especially after Oye Lucky and Dev D, I had a red-carpet entry to whoever I wanted to work with. And this is not just because I had successes behind me. Also because I was so-and-so’s son, nephew, brother…”

Which puts him in a strange ‘middle’, in the nepotism debate, that is usually conflated to the ‘elite versus masses’ battle, pitched in the wider political/public space. Deol’s “anger and rebellion” within the family itself, he says, was his reaction to fame and its pitfalls. Something he had watched closely, growing up. Left to him, it appears, he’d rather be anonymous, but remain an actor — obviously a misnomer.

“I was born an insider, but I pretty much lived as an outsider,” says Deol. That said, his debut film was a joint-family release, from Vijayta Productions — mainly helmed by cousin Sunny, son of Uncle Dharmendra.

Interested in debutant Ali’s script, he took him to meet Sunny, who was happy to hop onboard the film, since the lead character was a lot like Abhay himself! Such is how Socha Na Tha was born, and two amazing careers took off. Only the film, that released during the low-key “exam-time, March” wasn’t hugely promoted as the proverbial ‘star is born’. Socha Na Tha is hugely loved still.

Which reminds me, why is the Deol firm named Vijayta in the first place? “On my sister, my cousin — she is younger to Sunny Bhaiya. So, it’s Sunny Deol, Vijeta and Bobby Deol? “No. Then there is [another sister], Ajeita. Then there is Bobby.”

Abhay’s father, late Ajit Singh Deol (Dharmendra’s brother), I hear, was also an actor. Except I couldn’t quite find a clip online to support this, I tell him. He smiles, “He did two movies, one of which he produced. They were all in the ’70s. One never got made. I remember Honey Aunty, Zoya’s (Akhtar) mum said the cutest thing to me once. That my father is the reason her film didn’t release. I was like, ‘What do you mean?’ She said that he had to hold her face, and he was shivering [through the scene]. She was the leading lady in that film. I didn’t even know it, because I never saw that movie!”

Insider-outsider is anyway a time/generation construct. Many of the outsiders Deol worked with at the beginning of his career are bona-fide insiders now. And maybe that’s what the revolt is about — to eventually get to the high table. The cycle continues.

“You hit success, then it doesn’t matter if you’re insider, or outsider. They all want to work with you. You have to understand it is also very cliquish — you are part of this, or that camp. I had access to all of them, but I was like, no!”

Living in the Deol household, he also had no “Bollywood Juhu gang” friends. Barring his schoolmate, director Vikramaditya Motwane, who wasn’t “Bollywood then”!

Everyone goes through their brash 20s — sometimes it lasts longer — “You wanna change the world!” I asked Deol what he thinks of, when he looks back at that decade, after which it appears, the world changes you, one way or the other!

Some of the things he says he’s learnt is being diplomatic —“also, not equating power and money, with corruption — that needn’t always be the case. Money is like energy, and it is something that you know you can make good use of — when you have a lot of it. I could do things a little smarter, to not be taken advantage of, or be gas-lit.

“Human condition is complex. Everything we have spoken about today are not black and white. You would think you’ve heard it all. There was a lot left out. Also, I am really lucky. I know I did create lot of trouble, but it was all intended for the right purpose. And I created change. People still refer to films I did 10-15 years ago.”

Which is true, once you glance at his filmography until 2013, starting 2005 — those who were born that year turn into adults in 2023, when we’re making this conversation with Deol, 46.

Also, in the intervening years, so much has changed with films itself: “The disruption we were looking at got brought in by technology itself.” So the ‘multiplex movie’ became ‘OTT content’.

Also, the Bollywood indie started hitting Rs 100 crore collections, with the likes of Ayushmann Khurrana, Rajkummar Rao. Deol was the OG ‘OTT star’, even before there were streamers: “I am not done yet. Maybe what I did was 20 years ahead [of its time]. Those 20 years have come!” Only the intentions may not be matching the outcomes for some time.

And then you watch Deol in Prashant Nair’s Trial By Fire on Netflix — a performance so subconsciously chilled, yet powerful. Without once making an unnecessary show of it. The series on the Uphaar Cinema fire tragedy is still about subtle and solid story-telling, that therefore makes the leads, the stars. Fair to say: welcome back, Abhay.

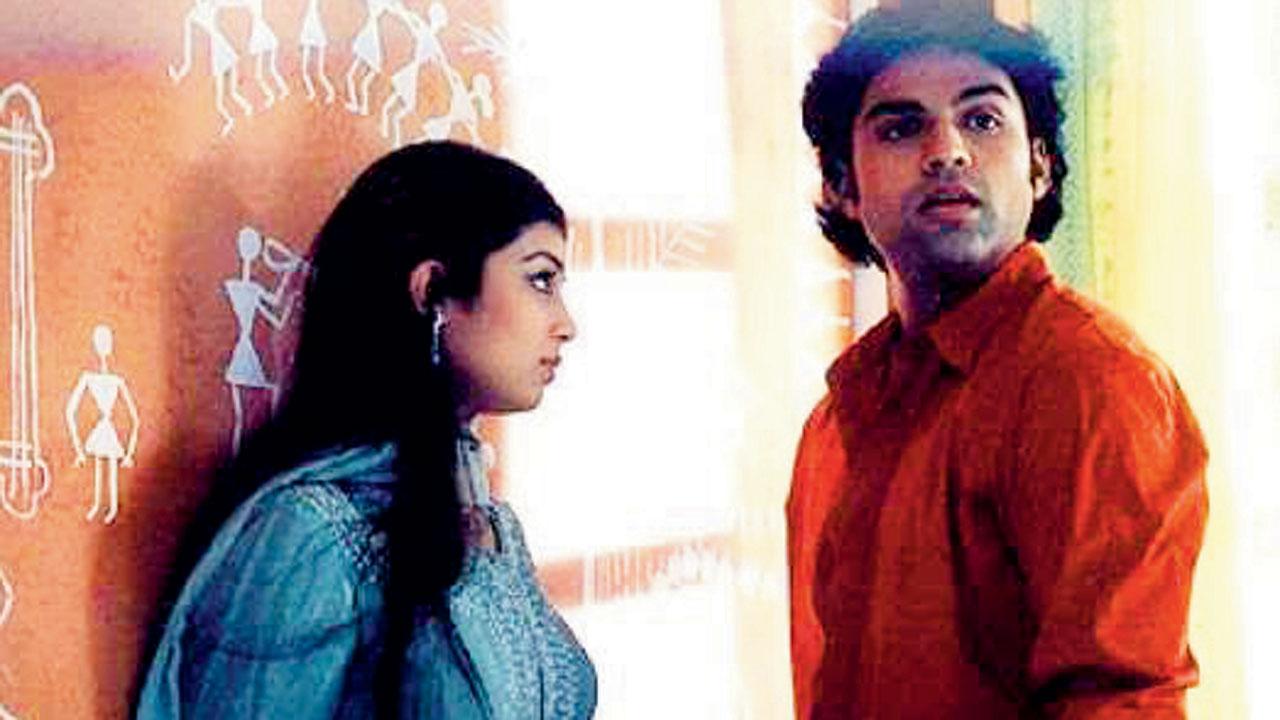

Abhay Deol and Rajshri Deshpande in Trial By Fire, which is based on the 1997 Uphaar cinema fire tragedy

Still from Socha Na Tha (2005)

Shanghai (2012)

Abhay Deol with Anurag Kashyap, Kalki Koechlin, and Mahie Gill during the promotions of Dev D (2009)

This entry was posted on October 4, 2009 at 12:14 pm, and is filed under

Abhay Deol,

Abhay Deol father,

Abhay Deol interview,

Anurag Kashyap,

Dev D,

Imtiaz Ali,

Interviews,

Oye Lucky Lucky Oye,

Shanghai,

Socha Na Tha,

Trial By Fire,

Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara

. Follow any responses to this post through RSS. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Post a Comment