Blockbuster films from the South release across India simultaneously; experts talk about why this is a good thing

8:48 AM

Posted by Fenil Seta

Heena Khandelwal (MID-DAY; July 31, 2022)

The concept of a pan-India film release isn’t new, say most film trade analysts and exhibitors. Mani Ratnam did it with 'Roja' (1992) and 'Bombay' (1995)—both Tamil films dubbed into Hindi and received well in North India. 'Hum', did it even earlier, in 1991. The movie starred superstars from both ends of the country—Amitabh Bachchan and Rajinikanth—and became one of the highest grossers of the year. Then 'Baahubali', both 'The Beginning' (2015) and 'The Conclusion' (2017), changed the game.

“It was a huge success,” says film trade analyst Komal Nahta. “Even today, 'Baahubali' is the highest-grossing Hindi film even though it is a dubbed one. No original Hindi film has been able to outdo it. Every South Indian producer wants to get on this bandwagon because the costing is minimal. You just have to record Hindi songs and dub the dialogues; nobody is spending Rs. 5 crores on promotions in the Hindi market. And if the film clicks, it is a huge profit margin.”

Calling 'Baahubali' a wake-up call for South Indian filmmakers, film trade expert and exhibitor Vishek Chauhan notes that the problem was that they assumed the market was saturated. It was further maxed out by increasing ticket prices to compensate the stars’ fee, which Chauhan says, is “huge, almost at par with Bollywood”.

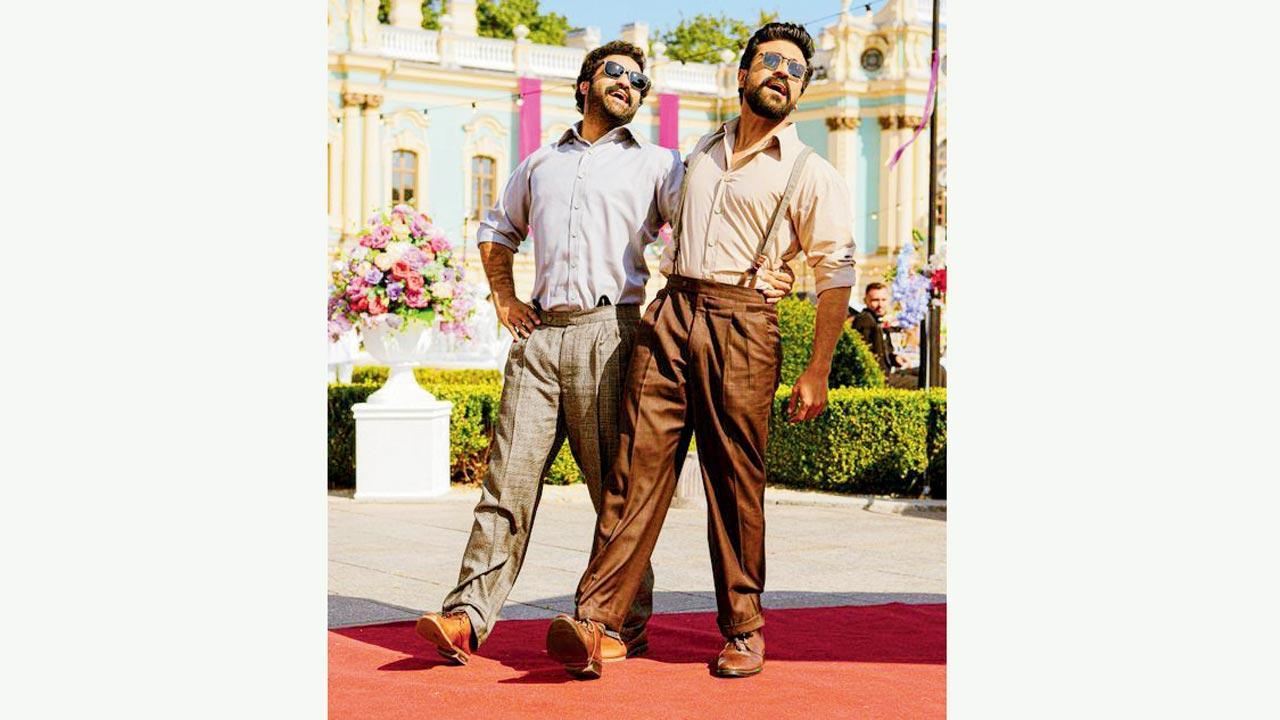

“But Baahubali’s success showed them a huge market,” he says, “Plus, Bollywood had stopped catering to the masses for a few years, and was looking only at the niche and elite market. This allowed South Indian films a backdoor entry. YouTube and Satellite TV is full of dubbed South Indian films, which has made actors from the South—Allu Arjun, Ram Charan, Vijay Sethupathi, and others—a household name in the North. With 'Baahubali', they uncovered their clout and muscle at the box office and flexed it with both the instalments of 'KGF' [2018 and 2022], Saaho [2019] and 'RRR' [2022]. 'Pushpa: The Rise' [2021] was like a bolt from the blue. Even Vikrant Rona’s opening is surprisingly good.”

Film exhibitor Akshaye Rathi agrees: “It was an absolute misconception that people weren’t looking for mass entertainment. A huge chunk of the audience doesn’t have too many avenues for outdoor recreation. While a certain section can go to a nice restaurant or to watch a play, for the audience at large, cinema is the only leisure activity with friends and family. In tier 2 and tier 3 cities, the prevalent recreational activity is going to movies. This section is about 75-80 per cent of India’s population. Filmmakers have been depriving them of an appealing genre of entertainment. And, now that we are giving it to them, they are lapping it up in big numbers. We have seen that with 'Sooryavanshi' [2021], 'Pushpa', 'KGF', 'RRR', and even 'Bhool Bhulaiyaa 2'.”

To him, it makes economic sense for a filmmaker to look at the whole country as the market, considering India has fewer screens per million (between 8 to 10 screens, against USA’s 124).

“If we further divide deployment of content on the basis of language, we limit the potential of our business,” Rathi says “OTT has enabled access to so much diverse content so suddenly that the audience is familiar with content made in any state. That’s why crossing this bridge has become easier.”

What does this mean for Bollywood? Stop taking the audience for granted, echoes everyone. “Going to a theatre is an expensive affair in terms of money and time, so the audience wants value for money,” notes Chauhan, adding that post the pandemic, only films that appeal universally do well in theatres.

“COVID-19 changed the market entirely—a shift that would have taken place over a decade, happened in two years. The audience is not shy to explore a different genre, hero, language, or market. OTT has made the film business a level-playing field. Even in Hollywood, only big hero films do well theatrically; others are coming to OTT.”

“This [South Indian films releasing across India] helps us up the bar for storytelling and technology. 'Baahubali', 'KGF', 'RRR', are all technologically extraordinary. I hope the upcoming films—'Brahmastra', 'Pathaan' and 'Tiger 3'—do well, considering they have similar grandeur and ambition. In a way, it made us realise that commercial cinema remains intact,” says film director and writer Milap Zaveri, adding, “At some point, commercial cinema was looked down upon by critics and elite people in cities like Mumbai. So films were made keeping critics in mind and high end multiplexes. Somewhere along the way, we stopped catering to the masses. Every commercial film may not work, but one failure shouldn’t stop us from doing it again. Even in the South, after RRR, Ram Charan released Acharya [2022], which didn’t do well; but that doesn’t stop the others because that’s the base of their industry. This pan-India release phenomenon is a wake-up call. Post pandemic, if people invest time and money in a film, they expect a spectacle. Even Hollywood is ruling the roost with the Marvel series.”

Interestingly, the OTT space remains unfazed, says Sidharth Jain, former creative head for Hotstar and founder of The Story Ink, the largest book-to-screen adaptation platform. “Bollywood is making the classic mistake of copying content from the South again,” he says. “Instead, they should understand that the audience wants to watch compelling stories, and that films that do well don’t follow a trend. OTT has always offered a buffet, so there is no threat to one particular kind of content. But yes, they are commissioning more series for the Southern market.”

This entry was posted on October 4, 2009 at 12:14 pm, and is filed under

Akshaye Rathi,

Baahubali,

Bollywood News,

Brahmastra,

Komal Nahta,

Milap Zaveri,

Pathaan,

RRR,

Sidharth Jain,

Tiger 3,

Vishek Chauhan

. Follow any responses to this post through RSS. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Post a Comment