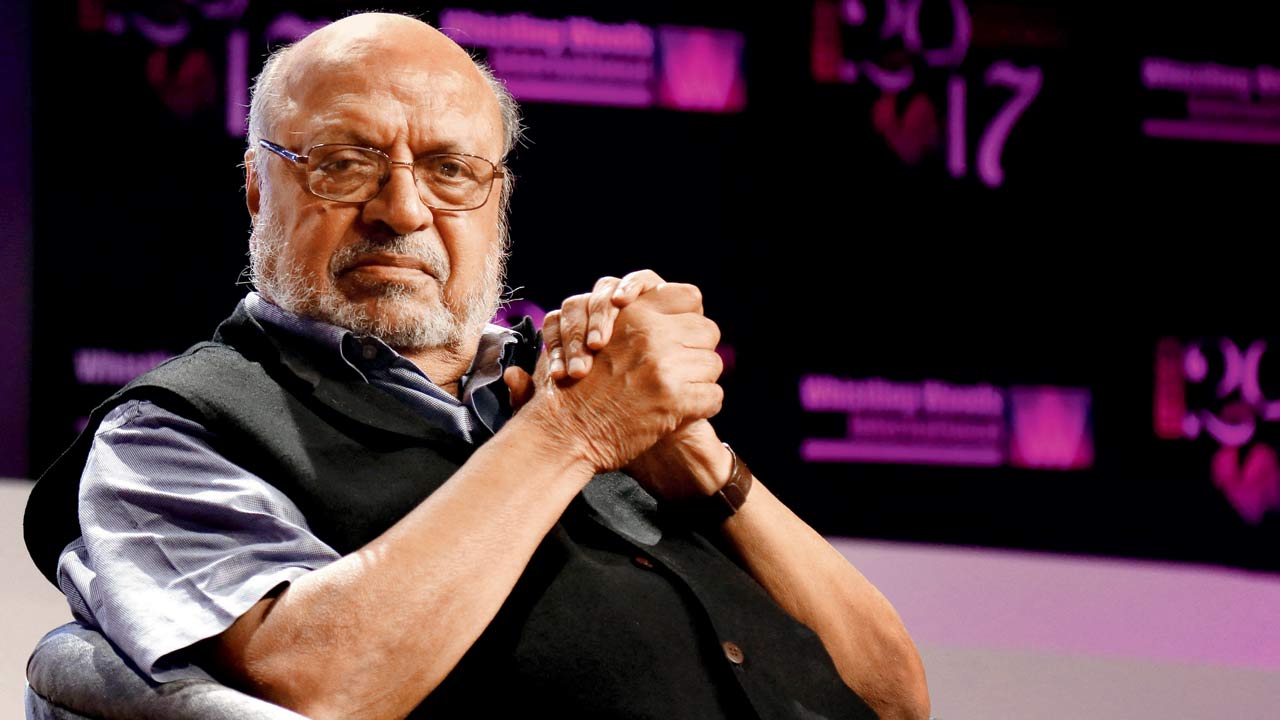

A junoon without parallel: Shyam Benegal sowed Ankur of new cinema, rediscovered Bharat

8:13 AM

Posted by Fenil Seta

Benegal Pioneered New Wave Cinema, Created Cult Classics

Sunil Nair (THE TIMES OF INDIA; December 24, 2024)

Shyam Benegal came out of nowhere and lit up the Hindi film scene in the 1970s at a time when the industry was "an absolutely closed shop", as a close associate recalled it. It was the age of melodrama and action - 'Roti Kapda Aur Makaan' and 'Sholay' were big hits - and every release flaunted a roll-call of stars. "There was no possibility for any young filmmaker to get into it at all," is how Girish Karnad, who was then director of the Film and Television Institute of India, described it.

Benegal's neorealism struck a deep chord with a generation keen on films that would mirror the social and political tensions of their time. His debut film 'Ankur' (The Seedling), a tale of sexual exploitation set against a feudal background with a cast of unknown yet riveting newcomers, ran 25 weeks at the landmark Eros theatre in Bombay. He had begun writing the script of 'Ankur' when he was in college in Hyderabad and spent 20 years looking for a financier before an ad film distributor agreed to produce it. Its success staked out new ground for the 'art/parallel cinema' movement that over time showcased new talent such as Naseeruddin Shah, Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil, Om Puri, Govind Nihalani, Vijay Tendulkar and Vanraj Bhatia.

Benegal, who pioneered parallel cinema in India and created the 53-episode Bharat Ek Khoj, and whose last project was a 2023 biopic on Mujibur Rahman - 'Mujib: The Making Of A Nation' - passed away in a hospital in Mumbai, days after he turned 90 on Dec 14.

Shyam Benegal grew up in a cantonment town near Hyderabad in 1930-40’s where his father, a professional still photographer, introduced him to the camera. The obsession with movies began early, his appetite whetted by Hollywood and Indian releases screened at a local hall for the morale of the troops. “There used to be two programme changes a week,” he once recalled. “…like in Cinema Paradiso, I befriended the projectionist so I could see both...”

Shifting base after his education, he began working at Lintas in Mumbai as a copywriter. The next decade and a half were spent on a prodigious number of ad films and documentaries. Traces of the social concerns underpinning his cinema are evident in the shorts he made, including the earliest ones, such as A Child Of The Street, which took a compassionate look at juvenile vagrancy, and Close to Nature, a colourful take on tribal life in Madhya Pradesh.

His stint as a teacher at the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) drew him closer to celluloid. But his bleak stories still had no takers among financiers. Lalit Bijlani of Blaze Advertising eventually stepped in. Both Ankur and Nishant, which came a year later, were set in the feudal lands of Telangana, a region under the Nizam. It was a world Benegal had seen up close in his formative years. Touted as his most striking works, the narratives and characters were situated in a rural milieu with a distinct dialect and attendant class-caste equations. Coming around the time of the Emergency, the two films spurred a movement of sorts and cemented his reputation as the high priest of the ‘New Wave’.

Benegal’s eclectic interests showed in the diversity of subjects. From Gujarat’s milk cooperatives (Manthan) to the life of a silent film era actress (Bhumika), from 1857 (Junoon) to feuding business families (Kalyug), his projects spanned periods and themes. A bearded, Renaissance figure at the centre of the ‘art film’ circuit, he was equally a mentor to actors, musicians, writers and technicians.

At a felicitation to celebrate Benegal’s 25 years as a filmmaker, actor-playwright Girish Karnad spoke of his innate ability to help artistes tap their potential. “He was not just a director but also a doctor, a psychiatrist, a father figure and a banker,” said Karnad.

The latter part of Benegal’s career was marked by biopics, including one on Gandhi’s years in South Africa and a tetralogy on Muslim women (Mammo, Sardari Begum, Hari-Bhari and Zubeidaa). By then, the ‘art film’ movement had dissipated. He had turned to a new set of collaborators, many from commercial cinema. His standout work in this period, however, was a part elegiac, part quirky interpretation of a Dharamvir Bharti novel, Suraj Ka Saatvan Ghoda. Occasional forays into television too made for interesting viewing: Bharat Ek Khoj, the mega-series based on Jawaharlal Nehru’s Discovery of India, and Samvidhaan, on the making of the Indian Constitution, were the best examples.

Benegal’s influence on the Indian film industry extended far beyond his own body of work. He headed a govt committee set up in 2016 to streamline the film certification process and lay down a framework that would allow more room for artistic expression.

--------------------------------------------

'Benegal told raw & real stories about ordinary people'

Bella Jaisinghani (THE TIMES OF INDIA; December 24, 2024)

Mumbai: The passing of Shyam Benegal, the torchbearer of New Wave cinema, evoked a lament of loss across the film fraternity Monday night. It was Shyam Babu who discovered and mentored an entire generation of the finest natural actors including Shabana Azmi, Naseeruddin Shah, Smita Patil and Om Puri, having fathered the parallel cinema movement with 'Ankur' in 1974.

In fact as recently as Dec 14, the entire clan met to celebrate Shyam Babu's 90th birthday, with happy pictures featuring Azmi, Shah, Kulbhushan Kharbanda, Kunal Kapoor of Prithvi Theatre, Divya Dutta and Rajit Kapur.

Filmmaker Shekhar Kapur posted: "He created 'the new wave' cinema. Shyam Benegal will always be remembered as the man that changed the direction of Indian Cinema with films like Ankur, Manthan and countless others. He created stars out of great actors like Shabana Azmi and Smita Patil. Farewell my friend and guide."

Actor Manoj Bajpayee whose career was baptised by his prince's act in 'Zubeidaa', termed it a "heartbreaking loss for Indian cinema. Shyam Benegal wasn't just a legend, he was a visionary who redefined storytelling and inspired generations". Actor-singer Ila Arun said, "I feel as if I lost my father. It is the end of a golden cinematic era."

Filmmaker Mahesh Bhatt said, "Shyam Benegal was a giant of Indian cinema. He told stories without pretense. They were raw and real, about the struggles of ordinary people. His films had craft and conviction. He changed Indian cinema, not with noise, but purpose."

Filmmaker Sudhir Mishra said, "Not many talk about the fact that there was a lament in his films and a sadness about the fact we were not living in the best of all possible worlds."

People from all walks of life mourned his loss. Congress leader Rahul Gandhi said, "Saddened by the passing of Shyam Benegal ji, a visionary filmmaker who brought India's stories to life with depth and sensitivity. His legacy in cinema and commitment to social issues will inspire generations. Heartfelt condolences to his loved ones and admirers worldwide."

Congress MP Shashi Tharoor recalled how Shyam Babu during his early years as ad filmmaker had photographed his sister and other children as "the first Amul Babies".

(With inputs by Swati Deshpande)

--------------------------------------------

He leaves behind a body of work so sprawling—shorts, documentaries, features, TV movies, series—that his CV alone might be longer than an obituary

Mayank Shekhar (MID-DAY; December 24, 2024)

Shyam Benegal’s last work, Mujib (2023), was possibly the most important film for Bangladesh; a biopic on the neigbouring nation’s founder, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. He was 89, when the movie released. You did well, Mr Benegal. His first feature, Ankur (1974), was possibly the most important Hindi film for India’s art-house movement, heralding the Indian New Wave, from Bombay.

In between is a life so full of all kinds of cinema—shorts, documentaries, features, TV movies, series—that his CV alone, let alone its range, might be longer than an obituary can do justice. This would include a series of firsts; again, starting with Ankur itself, that was actor Shabana Azmi’s screen debut. Nishant (1975) was Naseeruddin Shah’s. He picked both actors, after they’d graduated from Pune’s Film & Television Institute of India.

One evening, while watching news on television, the anchor caught his eye, and he cast her in his children’s film, Charandas Chor (1975). That was Smita Patil. Bhumika remains, arguably, her greatest performance. Between Naseer, Shabana and Smita, forming an alternate, Bombay star-system of their own—besides Om Puri (Susman, Arohan), Anant Nag (Konduran, Kalyug), Rajit Kapur (The Making of the Mahatma, Suraj Ka Satvan Ghoda), and so many others—Benegal didn’t just make films.

He built an entire eco-system, for what came to be known as Hindi parallel cinema. Named such, because it did not intersect with the Bombay mainstream—remaining true to its realism, social consciousness, barely appeasing to audience’s baser instincts, or ignoring its intellect, while staying within commercial cinema, after all, for his features were still mostly privately funded (Blaze Productions, in particular).

An unassuming, gentle soul, gifted with gravitas, foremost, Benegal was a young mind. How else do you explain a career scripted over seven decades. Consider that when he made his first short, in 1962 (Ghar Betha Ganga), Jawaharlal Nehru was still India’s Prime Minister; man was several years away from stepping on the moon; and it’d be 20 years before we’d get Doordarshan (DD) for a proper national broadcaster.

Last checked, Benegal was still making movies. His partner, Nira, both in life and films, was his sounding board. He gave DD, and indeed Indian television, its greatest OTT slow-burn, decades before there was OTT, with Bharat Ek Khoj (1988), based on Nehru’s Discovery of India. He made India’s crowd-funded film, Manthan (1976), based on the life of dairy engineer, Verghese Kurien, with contribution of 500,000 farmers, decades before crowd funding became a term.

With Junoon (1979), he made the sharpest effort, until then, to take art-house into a big-budget space, with stalwarts of the time, adapting Ruskin Bond’s A Flight Of Pigeons. At the turn of the century, when multiplexes offered a short-lived window into exploring meaningful yet entertaining content, beyond simply the starry space, he brought forward intelligent comedies, Welcome to Sajjanpur (2008), Well Done Abba! (2009).

This is before he swiftly switched gear, and embarked on the astoundingly ambitious series, on the making of the Indian Constitution, Samvidhaan (2014), for Rajya Sabha TV. Yup, Benegal has always been there. Not just in terms of works, but also for how he inspired. What’s the final shot in Nagraj Manjule’s Fandry (2013), if not the stone-throwing finale of Ankur!

Given the widest possible gamut, surely, everybody has a Benegal Top 10. And each might read so different from the other. Kalyug (1981), modern adaptation of Mahabharat, set in Bombay’s corporate world, tops mine; Mammo (1994) might be a second; Mandi (1983) could be yours, or Zubeidaa (2001), if you’re younger.

A cousin of Guru Dutt, who got interested in cinema, because of his photographer-father Sridhar Benegal, who gave him access to a movie camera, when he was only 12—once Benegal moved to Bombay, from Hyderabad, he started out as a man of advertising.

It’s something he shared with Satyajit Ray, his inspiration of sorts. One of the most enlightening conversations on cinema that Benegal left behind for film buffs was his interview with Ray himself, for a documentary (that occasionally appears and disappears from YouTube).

It’s where you see Benegal for simply a curious movie mind. And a consummate movie buff, you would always spot at screenings at cinemas and festivals. The last I met him, in 2019, at his Tardeo office, which is a shrine of sorts in filmmakers in Mumbai—it was right after his Manthan actor and long-time associate, Girish Karnad, had passed on.

“Everybody’s leaving now,” he said. The very next minute, he began revealing how the then Bangladesh PM, Sheikh Haseena, had entrusted him with a film on her father, Mujib, along the lines of Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi. Benegal was 85 then—speaking about recommendations to the Indian censor board that never got implemented, or his public commitments in Goa, initiated from his Member of Parliament fund.

We discussed movies as a changing medium. He told me the cellphone was the best way to watch films—the eye’s distance should, anyway, be one and half times the length of the screen’s diagonal, and the sound doesn’t get better than a headphone. I’ve followed his advice since. There was so much more to learn. The movies remain. He lives on forever.

This entry was posted on October 4, 2009 at 12:14 pm, and is filed under

Ankur,

Bollywood News,

Film and Television Institute of India,

Girish Karnad,

Lalit Bijlani,

Mahesh Bhatt,

Manoj Bajpayee,

Mujib: The Making Of A Nation,

Nishant,

Shekhar Kapur,

Shyam Benegal,

Smita Patil

. Follow any responses to this post through RSS. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Post a Comment