If you don’t make difficult films, you’ll have a dumb audience, a dumb voter-Sudhir Mishra

8:12 AM

Posted by Fenil Seta

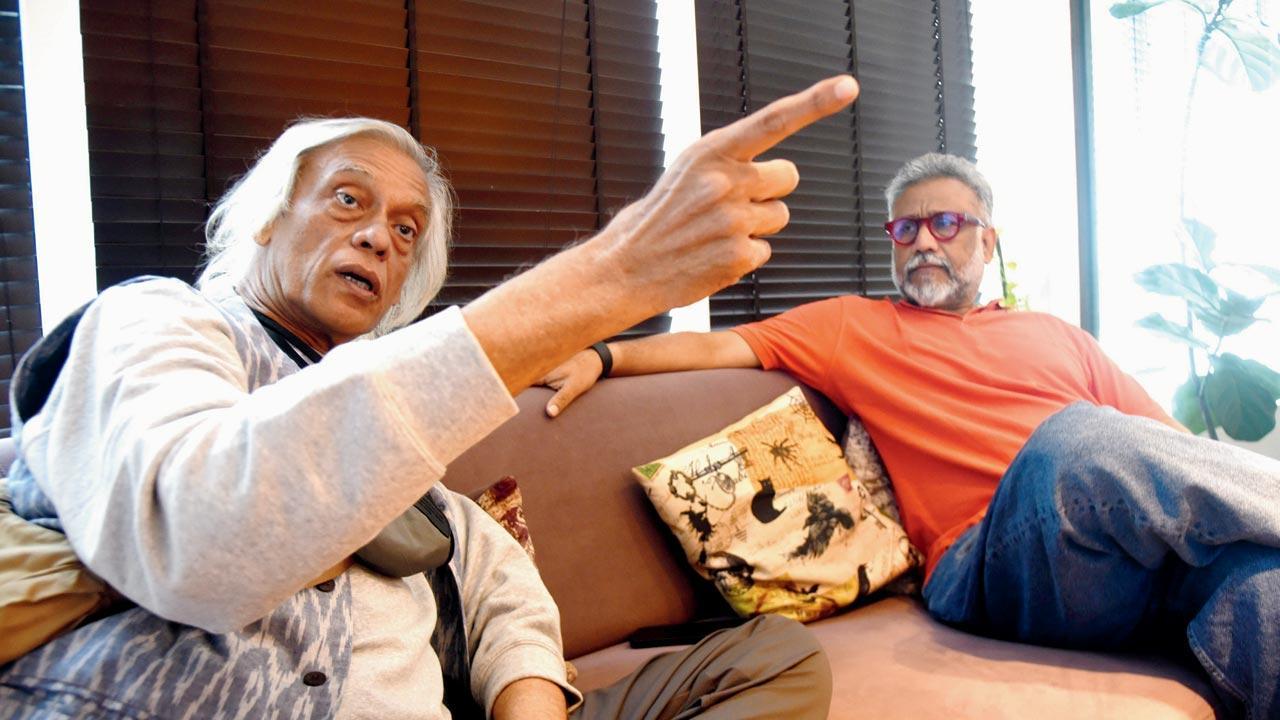

Sudhir Mishra and Anubhav Sinha, friends and collaborators on last week’s political thriller that chases the life of a rumour, on why they don’t waste time on apprehensions

Jane Borges (MID-DAY; May 14, 2023)

The day we visit Sterling theatre in Fort for an 8 pm show of Sudhir Mishra’s Afwaah, #LoveJihad has been trending largely thanks to the week’s other controversial release, The Kerala Story. It tells the story about a group of women from the southern state who are converted to Islam and forced to join the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Mishra’s film, a plausible antithesis to this rhetoric, appears light years away from this shor sharaba.

Afwaah is not unbothered, though. When we walk out of the cinema, we realise that it’s deeply invested in the great affliction of our times—the boom and doom of virality and the nature of communal propaganda. With characters caught in the thick of the white noise on the web, the film cleverly chooses to play spectator instead of taking the moral high ground as commentator. “Here’s a town. Let’s witness the chaos,” it seems to say.

Set in a conservative pocket in Rajasthan, the plot tracks the insincere and raving-mad aspirations of right-wing politician Vicky Bana (Sumeet Vyas), whose chicanery forces his outraged bride-to-be Nivedita Singh (Bhumi Pednekar) to run away from home—she won’t marry a bigot. This fuels a night of violence and bloodbath. Wedged in this kerfuffle is the suave Rahab Ahmed (Nawazuddin Siddiqui), who is on his way to a tony book festival where his wife is a participant, and whose only fault is wanting to rid himself of the guilt of a lie he has carried far too long. It’s what—we will later learn—compels him to save Nivedita from the goons set loose by her fiancé. It’s a trap, and for a man, who doesn’t wear religion on his sleeve, but whose identity now embroils him in a “Love Jihad” controversy.

“He is being hunted for who he is not.” The audience is pulled into a night of epic proportions. “A lot of people wanted me to remake Iss Raat Ki Subah Nahin…,” says Sudhir Mishra of his iconic 1996 thriller that spans an entire night, explaining the genesis of his latest all-nighter, when we meet him days after its release. Mishra is joined by friend and Afwaah’s producer Anubhav Sinha, “…But you can’t go back to your youth, and remake a film just like that.”

The idea for Afwaah “was all over us. You just had to have your ear to the ground”. “But what interested me, and what I think the critics have not got…” says Mishra, asking us if he can be “a bit arrogant” “…is that people see films only at the surface.”

“Afwaah is not really about the rumour that’s outside,” he says of the political thriller that most critics have called a cautionary tale about false narratives infesting social media. “Protagonist Rahab is also spreading a rumour about himself, and the bubble he is living in,” says Mishra, who has written and directed the film, “The film is not about what makes headlines, but what happens behind those headlines.”

Mishra’s characters are layered. We see spurts of goodness, even in evil. Chandan, a character played to perfection by Sharib Hashmi, believes he is Vichy Bana’s wingman; he makes one wrong move and has everyone baying for his blood, including Bana, who is ruthless in his chase. “Chandan is both, the victim and the antagonist. The film tries to understand the lyncher as much as it understands the lynched.”

None of his motivations as a storyteller, Mishra feels, have been understood by the critics. His disappointment is evident. But that’s not stopping him. “If you don’t make difficult films, you will have a dumb audience and a dumb voter… and then God help you.”

Sinha, who has been listening quietly, has himself long moved away from spinning box office juggernauts, to engage with content that forces the viewer to think. Be it the patriarchy-defying Thappad (2020) or the more recent Bheed, which documented the painful and horrifying migrant exodus during the pandemic.

Working with Mishra was an important part of this journey, he says. “Over the last few years, we bounced ideas off each other. But every film has its destiny, some stories get made quickly, some take longer. This [Afwaah] was the child that got lucky.”

Having said that, Sinha says, the content of the film was not as important, as “wanting to make a film with Sudhir bhai”. “He is one of the first filmmakers I met when I came to Mumbai. On my first night here, I had the privilege of having a drink with him and Javed saab… he used to drink back then,” Sinha smiles.

“I wanted to make Afwaah to learn something from him. The rest—you write a film, you cast for it, you shoot and edit—is all mechanics. What’s important to know is why you are making the film that you are.”

Movies like Afwaah that don’t endeavor to entertain the audience in a manner that they lose themselves, he adds, are difficult to make and watch. “What has become even more difficult [to determine] is which film has the real audience. All those numbers [box office] are not trustworthy. They are not truthful anymore. Unfortunately, the success and failure of a film is only defined by them,” says Sinha, “But what about the other number, the number of years a film will live on a shelf? Or the number of times, people will go back to it [during their lifetime].”

Film consumption is diverse. “It is meant for weekends, theatres, satellite channels, OTT platforms and for times to come. Of these, the biggest parameter, according to me, is the times to come,” thinks Sinha.

For Mishra, making a film is still a discovery. A mathematician’s son, he didn’t go to film school. He says he learnt from his father that you start with a hypothesis, and then you go about proving it. “I make a film to learn. I wanted to learn about Rahab... there’s a lie he has been telling.”

Mishra’s protagonist is not a hero in the true sense then. He doesn’t want to die, because he thinks it would be a useless death. “When did you last hear a hero say that?” Mishra asks.

“One journalist called me after seeing the film, saying it reminded her of George Bernard Shaw’s Arms And The Man, where there’s a character called [Captain] Bluntschli who says, ‘martyrdom sucks’. I suddenly remembered that Bluntschli was the first role I played in my life, on stage. So, what influences you, you sometimes discover through the process of making a film. I discover myself [when I make a film].”

That it is increasingly becoming difficult to make honest films that hold a mirror to society, is not lost on them. “I would be lying if I said that there wasn’t any apprehension,” says Mishra. “But I don’t think it ever stopped Anubhav from wanting to produce it, or me from making it. There is this dynamic, democratic society called India, and we are participating in it. We should be allowed to have our say. That’s what we expect.”

Mishra confesses that his affiliation is to his art, not any political party. His 2004 political drama, Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi, was set against the Emergency of 1975, and released when the Congress was in government. He is also not one to shy away from engaging in conversation with filmmakers whose films contrast his own.

We were surprised when we stumbled on a recent two-hour-long interview where Mishra engages with The Kashmir Files director Vivek Agnihotri for his YouTube channel, I Am Buddha. Here, Agnihotri, who is an unapologetic right-wing filmmaker, credits Mishra for inspiring him after Hazaaron... to tell the stories he believed in. No hard feelings, none at all.

The hope is that more people will show courage. Even actors, who are often hesitant to take on daring scripts. “See, the big stars won’t come to me anyway, because I write frail characters,” claims Mishra. “There’s all of Indian cinema. And then, there’s my cinema.”

The former, he says, worships the hero, while he is invested in their failure. “That’s why it is more difficult to make my kind of films. The heroes don’t like this. It upsets their testosterone-ridden, fake machoism… they are simply pretending to be sensitive to women. None of them are.”

Sinha thinks female actors are stronger in conviction and the risk that they will take. He adds that this also stems from the fact that we do not ascribe the success of the film to its women. “A lot of time it’s they who are responsible for it, though,” says Sinha.

Waheeda Rehman, for instance, says the duo, was “better than all the men of her time”. “She had more skillsets than any of the actors.” Sinha adds, “Even today, the number of good female actors is way higher than the good male actors. They are gutsier, and they are far more disciplined…”

Mishra adds, “I come from the parallel cinema [era] when we were considered a viral infection. Today, I feel that there are younger actors who are far more genuinely appreciative of the films I make. Whether they work in my film or not is another thing.”

Sinha and Nawazuddin Siddiqui, the protagonist of Afwaah

Mishra with actor Bhumi Pednekar, who plays a political heiress

This entry was posted on October 4, 2009 at 12:14 pm, and is filed under

Afwaah,

Anubhav Sinha,

Anubhav Sinha interview,

Bhumi Pednekar,

Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi,

Interviews,

Nawazuddin Siddiqui,

Sharib Hashmi,

Sudhir Mishra,

Sudhir Mishra interview,

The Kerala Story,

Waheeda Rehman

. Follow any responses to this post through RSS. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Post a Comment