Many people don’t know that Amitabh Bachchan’s role in Anand was initially offered to Soumitra Chatterjee-Suman Ghosh

8:23 AM

Posted by Fenil Seta

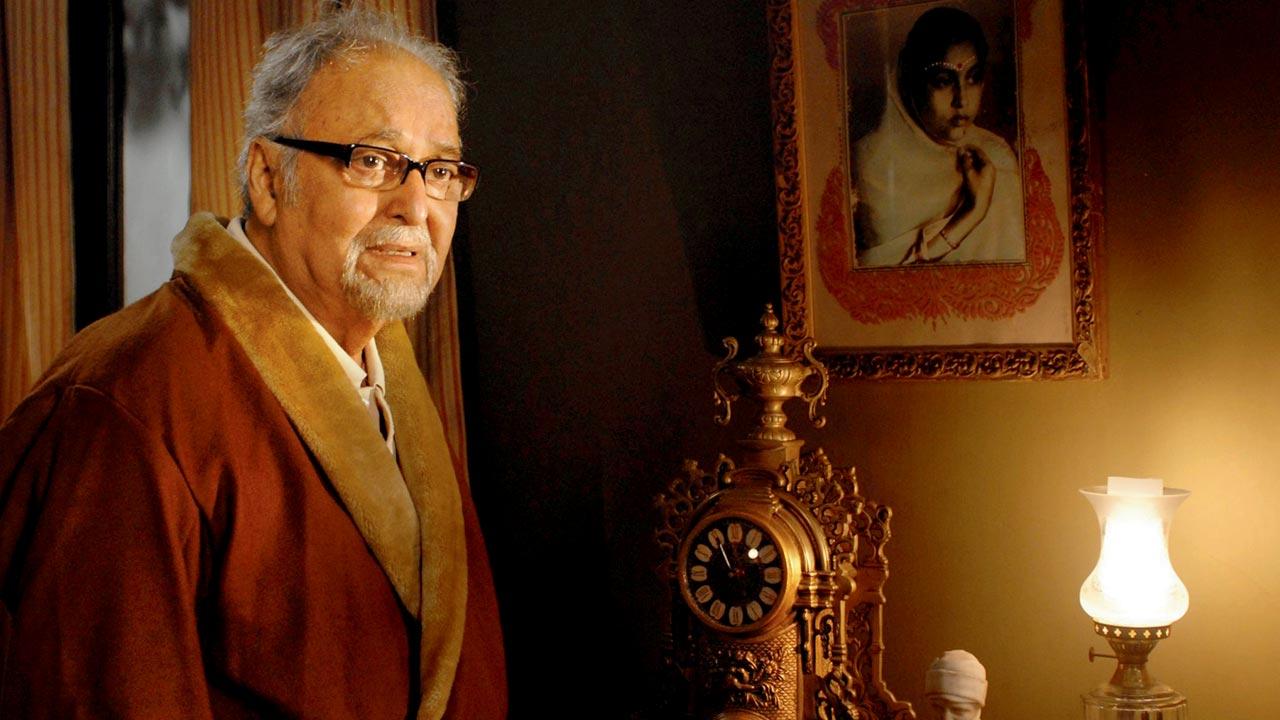

A filmmaker recollects experiences of working with acclaimed Bengali actor Soumitra Chatterjee in a book that aims to introduce him to a wider audience familiar only with his work with Satyajit Ray

Sucheta Chakraborty (MID-DAY; January 9, 2022)

In November 2020, in the days following actor, poet, playwright, painter and singer Soumitra Chatterjee’s passing, filmmaker and professor of Economics Suman Ghosh remembers being mired in sadness. Around this time, Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri, editor-in-chief at Om Books International, who had previously written on the themes of memory, ageing and death in Ghosh’s films with Soumitra Chatterjee, proposed the idea of a book on the director’s personal and artistic relationship with Chatterjee. While initially hesitant, given that the book would be a daunting one, not least because it would be his first, Ghosh realised that this would offer the cathartic release he needed at the time.

“Rather than lament his passing, I thought why not share my experiences with people and help them get an intimate glimpse of the man,” says the director. Soumitra Chatterjee: A Film-Maker Remembers, which released last week to commemorate the actor’s birthday this month, traces Ghosh’s observations and interactions through five films over 15 years with “the last of Bengal’s Renaissance men”.

Ghosh writes about being in awe of Chatterjee’s stature as he watched the actor during shoots at a time when he was still a PhD student at Cornell, eager to venture into filmmaking. “I never expected to form a personal relationship with him. He had achieved so much in life, why would he be interested in giving a hundred per cent in a film with a debutant filmmaker like me?” wondered Ghosh who cast Chatterjee in Podokkhep (Footsteps; 2006) about a retired man and his bond with a little girl in a film inspired by F Scott Fitzgerald’s story The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button about a man aging in reverse.

While the sharpness of his craft was expected, what surprised Ghosh about the thespian was his hunger to work with younger directors and with newer mediums and formats right till the end. There was also, he recalls, a child-like curiosity in him for the mysteries of life, a quality he says he has observed in other greats like Amartya Sen, the subject of an early documentary. He remembers how the last conversation he had with the actor was a few months before his passing when the actor, a well-known workaholic, was forced to sit at home during the pandemic.

“He was reading a book on the young Galileo, and discovering how his father who was a musician impacted him,” he shares. “I marvelled at this man who in spite of a pandemic ravaging the world and making people mentally and physically sick could still hold on to his sense of wonder.”

Everything from cricket and Garry Sobers to Satyajit Ray, the Masai tribes of Africa and the new Bengali literature and cinema interested him, he says, their conversations on these myriad subjects a generous source of nourishment for the director. “… It was as if he wanted to perpetually soak in the delirium of life and be bathed in all its beauty. His mind was like a blank canvas, ready to be painted with colours,” writes Ghosh in the book, pointing to how this receptiveness also informed his work as an actor.

In one of the book’s many interludes, Ghosh writes fondly about Chatterjee’s visit to his home and his mother’s trepidation over the lunch being served even as she grappled with the fact that the man she had watched growing up in such classics as Charulata and Apur Sansar would be in her home. Among other memories of the artiste Ghosh holds dear are those of his Rabindra Sangeet sessions with cinematographer Barun Mukherjee in between shots.

“Many people don’t know that Amitabh Bachchan’s role in Anand was initially offered to him by Hrishikesh Mukherjee and that Shashi Kapoor wanted to cast him in Junoon,” says Ghosh, when we ask him about how he thinks his book will add to the rich legacy the actor has left behind. While Chatterjee remained loyal to Bengal’s cinema, Ghosh believes that film lovers nationally didn’t get to appreciate his talent adequately.

Even directors like Shoojit Sircar and Anurag Basu tried to get him to act in Hindi films and lament that they could not take his talent outside Bengal which he deserved, he says. “He was probably more famous internationally than in India apart from Bengal, and the national audience too only knows him through Satyajit Ray’s films,” he says, his book offering a list of some of his favourite films not directed by Ray featuring the actor.

He was a popular star, he points out, delivering superhits as well as artistically refined films even in his 80s. “The book is a way to provide a glimpse of this person to a national readership so that they are inclined to follow up on his work,” says Ghosh. “That’s why I wrote it in English.”

This entry was posted on October 4, 2009 at 12:14 pm, and is filed under

Amitabh Bachchan,

Anand,

Anurag Basu,

Interviews,

Junoon,

Satyajit Ray,

Shoojit Sircar,

Soumitra Chatterjee,

Soumitra Chatterjee: A Film-Maker Remembers,

Suman Ghosh,

Suman Ghosh interview

. Follow any responses to this post through RSS. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Post a Comment