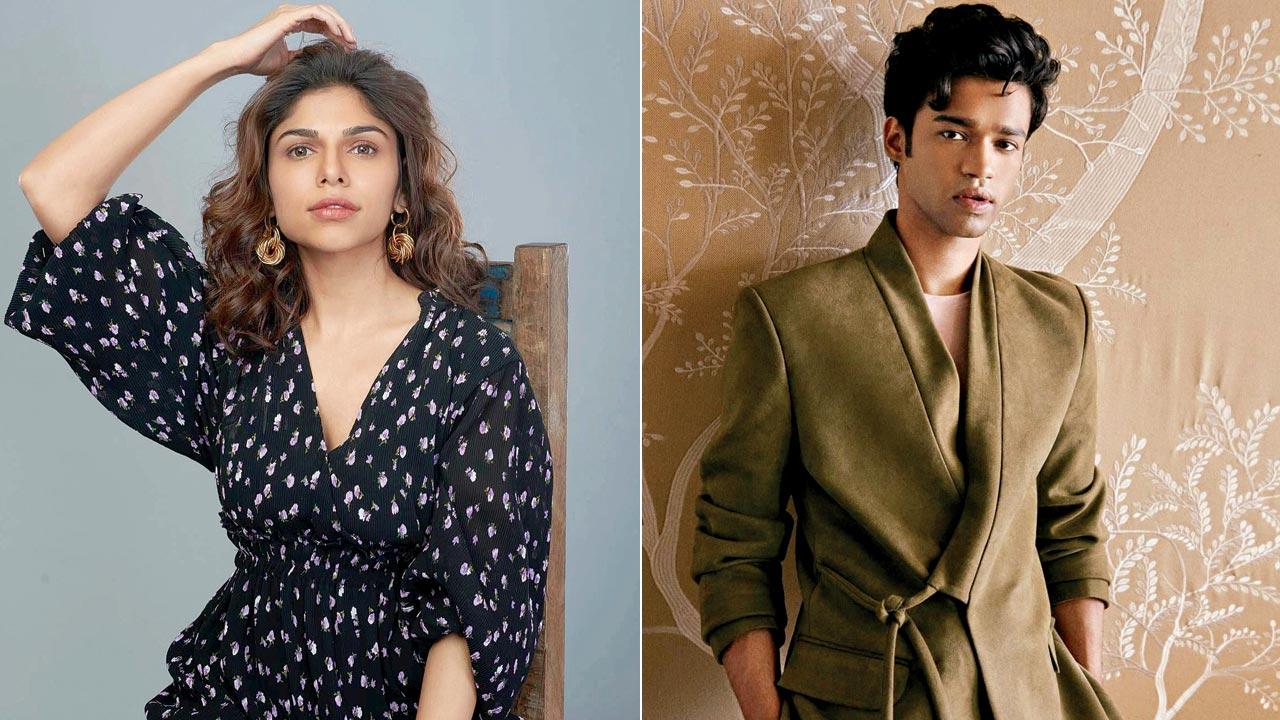

Experts talk about Sharmin Segal and Babil Khan's trolling: "The Internet has made being a****les cool"

8:26 AM

Posted by Fenil Seta

While a critic is concerned with the craft, a troll gets personal. And algorithm could be the reason the attacks on Heeramandi’s Sharmin Segal spiralled

Mohar Basu (MID-DAY; June 9, 2024)

It’s been a month since Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s ambitious OTT debut series Heeramandi dropped on Netflix and the one person who has been discussed the most is his 28-year-old niece, Sharmin Segal. This is her second project after Malaal, and the Internet has been picking away at her performance. Most reviews say Segal’s laboured performance sticks out next to that of seasoned colleagues. But the armchair critic on the ’Gram has also zoomed into the micro-expressions of colleagues as an unprepared Segal gives interviews.

Where does so much hate come from?

The industry consensus is that Segal and many young actors become soft targets for the Internet. “Hate for Sharmin comes from nepotism because she is Mr Bhansali’s niece,” says Tushar Joshi, a film critic with India Today. “In my interview, Mr Bhansali spoke about why he cast her. Alamzeb was meant to naïve, and if you watch the show with Sanjay’s words in mind, you realise that this was their vision for the character.”

Nikhil Taneja, mental health advocate and co-founder of Yuva (a Gen Z-focused media company) agrees that star kids have it worst. “The root of the vitriol towards Sharmin or Suhana Khan or Khushi Kapoor comes from the fact that people are struggling themselves; they naturally dislike those who have easy access. This happened with The Archies as well.”

While this normalized the conversation around nepotism, making it more than a passing discourse, it’s a fine line into harsh trolling. “The Internet has made being a****les cool,” says Taneja, “People need to understand that being unkind to people is not okay. To say that someone is a bad actor is understandable, but to shame people on how they look, behave and talk, you are projecting your understanding of the person.”

So much so that colleague Richa Chadha had to step in to shield her colleague to say, “Criticism has to be constructive. If someone doesn’t like your work, one could say, ‘okay the body language isn’t believable. [or] The voice tonality isn’t okay’. When we start operating like that, we help the actor grow. Actors bhi insaan hai, mental health sabka kharab hota hai.”

An image consultant adds, “The Internet and social media have simply allowed people to say things without being held accountable. We come from the culture of wanting to pull down the next.”

And, it doesn’t help, the professional says caustically that, “Gen Z stars want to be everyone except themselves. They invite hate by being inauthentic. If you are being hypocritical, you can’t cry about it.”

They say it may be their job to protect the client’s image, but that’s hard when they don’t have the personality they try to project. “A lot of it is their own doing,” the image consultant said, “They’re like: ‘Oh I wanna have Kareena’s sassy personality on the Internet’. You can’t become someone else if you are not naturally that.”

Recently, a clip went viral in which Babil Khan, actor Irrfan Khan’s son, is seen apologizing to a woman after he unknowingly bombed her red carpet pictures. One user wrote, “He makes Vanga look better as I can at least see straight forward toxicity”. Another said, “There’s something so spectacularly insidious about a man who makes a whole performance out of being nice. Like who even are u when ur not performing”.

Here, a digital content creator says, freedom of expression is rebellion against the careful curating of personalities. “Comedy is not bullying; it is a commentary,” she says, “My Babil Khan video did well because people are recognizing that his PR has a tendency of projecting him as a little saintly boy. He is already a kind, sweet, wonderful person; cut out the extra drama of buying memes saying, ‘Oh such a green flag’.”

She sees her role to be in line with the press’s: Cutting stars and their perceptions to size. “Be yourself, be authentic. Let us decide if you are a green flag,” she says.

However, Taneja, who shot with Babil last year, says, “He is a visibly anxious person. He has been very open about his grief, his mental health, losing his father so unexpectedly, his living parent. Being vulnerable has made him a soft target. His every move is analyzed, he has to live up to the pressure of carrying forward the legacy of one of the world’s greatest actors. People need to stop and analyse whether they are punching up or punching down. ”

Abhishek Thukral of the boutique PR Agency Hardly Anonymous Communications, says the hate for Segal is a case study on things going too far. And that it’s the publicist’s responsibility to coach a fresh actor on media perception, and check things when they go too far.

“No actor is great in every project,” he says, “And that’s okay. But when an actor is going for promotions of a big show or movie, they must be prepared better. There is a reason experts are hired to give sound advice to talents.”

He adds that young actors have to be trained in facing the press with mock drills to help them field questions better. “You can’t go into a Heeramandi underprepared,” Thukral says.

And in the case of someone who is being launched into the industry, a publicist’s role is to condition the audience to the new person. With star kids, it’s made to look organic with a slow trickle of snapshots from their personal life, with the more recognized or influential parent. “The world should be familiarized with the person before the launch,” says Thukral, “Who are they? What do they like?”

Where do film critics come in all this? In the era of social media, are they mindful of how far their words could travel? Are they aware harsh ones could set off a tsunami of hate?

“A reviewer’s job to take a movie or a show, recommend or fault it,” Raja Sen, film critic, says. “It is your informed opinion. You must present your perspective such that people have a solid idea as to why I like a certain show.”

The critic-filmmaker dynamic is professional, he says, and crucial for better storytelling. They serve as gatekeepers of entertainment and the craft. “Sometimes people in the movies think of criticism as a personal attack,” says Sen. “No it is not; we don’t know these people personally and we are reacting to the work, not the people. As critics, however, the review should lucidly explain what we are finding revolting so that the reader can make up their own mind.”

When the critic-audience-filmmaker is bound by this authentic service, everyone benefits. “Ram Gopal Varma once told me that bad reviews are the only ones worth reading,” continues Sen. “I am not telling a filmmaker where to start a scene; I am saying the movie was a traumatic experience for me. That should make them pause and ask why.”

Joshi agrees somewhat: “Reviews are feedback for course correction; I won’t write the person off. I won’t use harsh words; won’t slam beyond redemption. If a performance is abysmal, we need to ask ‘What isn’t working?’”

He agrees that the conversation is about the craft, not the person. “You ask if the actor getting better with their films, says Joshi, “It’s a conversation about Janhvi Kapoor right now, that her performances are of similar nature. I understand that the actor put themselves out there, [so] they have to be open to critique. But attacks can’t be of a personal nature.”

In a time when perception can be shaped through influencers, Sen believes the role of the critic is even more important. “When I look at criticism today, I see a lot of soft pedalling and pacifying in reviews. There are many agendas, many camps...” he says. “[So] the role of a reviewer is even more crucial now. A critic can’t be wishy washy. In order to stay relevant, they need to be honest.”

In many ways, Reels and other reactions on the Internet are the “authentic” response to this micromanagement of perception. “Through Reels,” opines Sen, “people are representing some authentic experience. It may not be cool, but they are true to their experience. The problem is that they are unfiltered, but they too are a work of passion.”

And once they are out there, algorithms take over, and everyone jumps on the trend to be seen. “We mirror the audience’s mood,” says content creator Arindam Thapliyal. “Our content only reflects what the public feels. Content creators are putting up videos only to stay relevant. They aren’t trying to attack any star.”

He says it’s the public mood that colours the conversation. “It makes a plain comedy video seem like an attack. The videos, if you notice say nothing; it is the comments that are hateful.”

Hate is best managed early, and the publicist we spoke to earlier believes Segal’s image spiralled out of hand. “Narratives can be controlled by buying media narratives, social media memes. The process of any damage control is different. If my client has said something elitist, ignorant, I would suggest acknowledging, apologizing and moving on. If it’s political, I suggest not meddling. If a newcomer is getting hate, you have to counter with positive narratives.”

Individual responsibility, unheard of on the web, will need to be practised soon. “The Internet is our second home and to keep it clean, hate free and non-toxic is as much our responsibility,” says Taneja. “It is not long before we all start being shaped by this hate.”

This entry was posted on October 4, 2009 at 12:14 pm, and is filed under

Abhishek Thukral,

Arindam Thapliyal,

Babil Khan,

Bollywood News,

Heeramandi,

Nikhil Taneja,

Richa Chadha,

Sharmin Segal,

Tushar Joshi

. Follow any responses to this post through RSS. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Post a Comment