I’d sleep under the porch of Khar railway station-Javed Akhtar

8:26 AM

Posted by Fenil Seta

Thrown out of his father’s Bombay home by his stepmother, lyricist Javed Akhtar in a new book tells Nasreen Munni Kabir how good friends and Cha-Cha-Cha kept him afloat in the city of dreams

MID-DAY (January 29, 2023)

Nasreen Munni Kabir: Can we go back to the time you first came in Bombay to settle down here? I remember you once told me you arrived on October 4, 1964. You were 19 years old and that’s when you began looking for work in films. What drew you to films?

Javed Akhtar: There was no shame for a writer to work in films because almost all the important poets and prose writers were working in the film industry at that time; they were either writing dialogue, screenplays or songs.

Don’t forget, my father was already working in films as a songwriter. He had not reached the position of Sahir, Shailendra or Majrooh Sultanpuri, although he was doing well. I must admit I did not try to get into films because of those great writers—frankly, I came to Bombay because Dilip Kumar, Dev Anand, Raj Kapoor and directors like Guru Dutt, Mehboob Khan, Bimal Roy and K Asif were working in films.

I thought the film industry was glamorous and I was seduced by the world of Hindi cinema and I wanted to be a director. At 19, one does not always have a clear plan. The only thing I was certain about was wanting the dialogue writer Akhtar-ul Iman to write the dialogue for my first film. He was a well-known Urdu poet and wrote excellent dialogue for many films, including B R Chopra’s courtroom drama Kanoon. It was a film without songs, which is still a rarity in Indian cinema. His lines for Nana Palsikar’s character in Kanoon were sharp and incisive.

Akhtar-ul Iman also wrote superb dialogue for Yash Chopra’s Dharmputra and Waqt. He won the Filmfare Award for Best Dialogue for both these films. His Flat No. 9 was disappointing and not up to his usual standard, but I made it a point to see all the films with his dialogue.

NMK: When you came to Bombay, you said you stayed with your father for only five days. Why only five days?

JA: In a fit of temper my stepmother slapped me and threw me out of the house. This happened in my father’s presence. She just didn’t want me around. And there I was, not even 20 years old, on the streets of Bombay with 27 naya paisa in my pocket.

NMK: Didn’t your father defend you?

JA: No. There’s no point talking about it now—what’s done is done. I was accustomed to living a paradoxical life for years.

Whenever I had to go hungry because I didn’t have a rupee to my name, I would dream of daal-chawal. In my mind’s eye, I’d see steam rising from the hot daal and marvel at the whiteness of rice. Why daal-rice? Was it my favourite dish from childhood? After many years, I understood why. When you have an empty stomach for more than 36 hours, you can have a lot of acidity, and so your body cannot cope with spices and wants plain and simple food. And that is why your mind fantasizes about daal and rice.

NMK: Besides sleeping hungry on some nights, you once told me you slept in a railway station. Is that right?

JA: Yes, I did sleep a few nights under the porch of the Khar railway station. If I had nowhere to sleep, I slept in parks and on pavements. Though, for the most part, I was welcomed in their homes by my many friends, including Javed Mahmood and his sister Zohra Jamal. Zohra Jamal was a short-story writer and a former student of my mother’s. After spending some weeks with them, my friend Parvez, who was a film publicist, and another friend, Kamal Anand, and I shared a room costing ninety rupees a month. We paid thirty rupees each. Parvez is no more now, but I am still in touch with his wife. Her name is Shibani, and at that time she was his girlfriend. Her sister’s name was Nazar. I used to call them ‘Chhoti behen’ and ‘Badi behen’ because the maid who came to clean their house called them by those names.

Even today, I have Shibani’s number in my contacts under the name ‘Chhoti behen’. We became friends. They belonged to an upper-middle-class family and generously took me to the movies and insisted I eat with them, so every night I landed up in their home. Shibani and Nazar often asked me to accompany them to fancy parties, some hosted by big industrialists, including the owner of Himalaya Bouquet. He had a huge bungalow in Powai that had a plaque on the gate that I will never forget: ‘We may be vegetarian, but our dogs are not.’ [both laugh] At these parties, I made my presence felt by cracking jokes and telling stories. People seemed to enjoy my company. That was a plus point.

NMK: I can sense how moved you are by the kindness of your friends and strangers. I believe it was thanks to some friends you even learnt ballroom dancing.

JA: Yes. We had a common friend, Kishan Tinani. He was a few years older than me, and he was a dancer, so Shibani, Nazar and Parvez asked him to teach us ballroom dancing. That’s how I came to learn it.

NMK: Were you a good dancer?

JA: I don’t claim to have been exceptional. I was pretty good. I have a sense of rhythm and was graceful enough. My favourite dance was the Cha-Cha-Cha. It was crazy—I was without a job, without money to pay the rent, and yet I was learning ballroom dancing and attending fancy parties, thanks to my friends. There are good people in this world. It is not made up of only bad people who want to harm or hurt you. If life has dealt you bad cards, sorry, tough luck!

NMK: I’m amazed you managed to retain your sense of humour.

JA: Maybe it’s because of those days that I have it at all! Shock absorbers in a car are not for smooth roads but for bumpy ones, for roads with potholes. A sense of humour is a kind of shock absorber. It is meant for bad times and comes in handy for making horrid moments tolerable.

Excerpted with permission from Talking Life: Javed Akthar in Conversation with Nasreen Munni Kabir, Westland Books

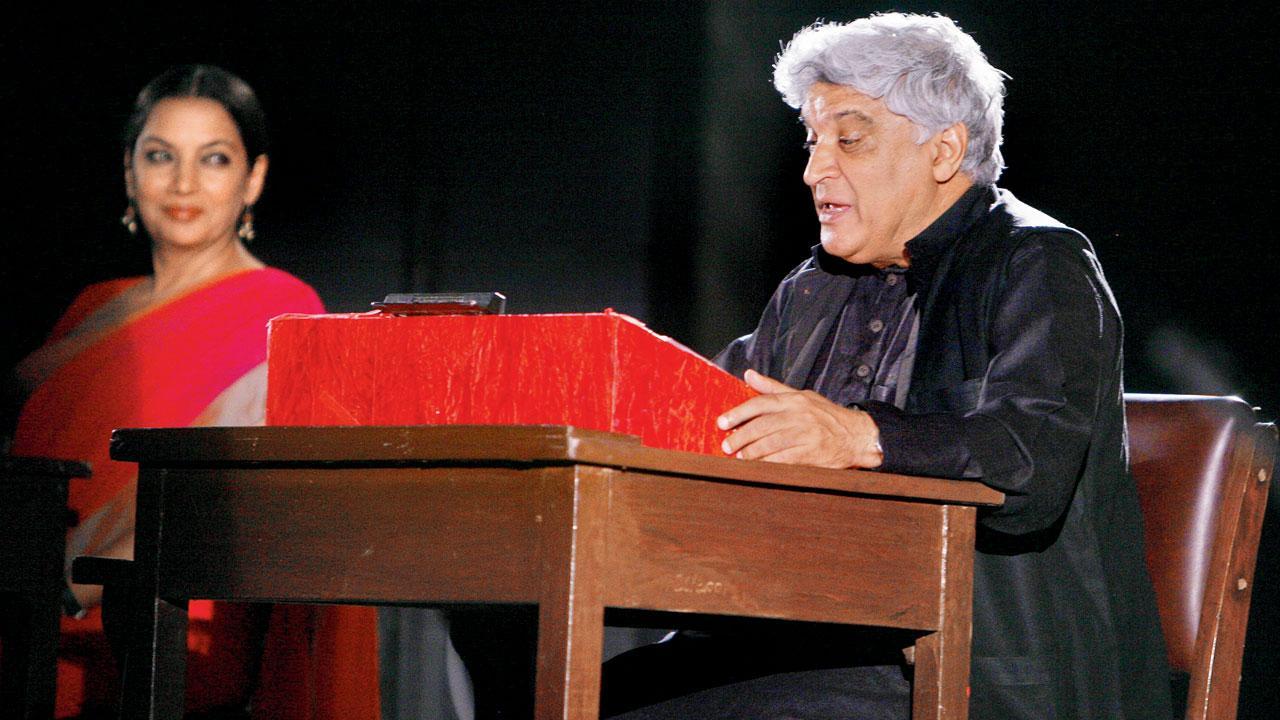

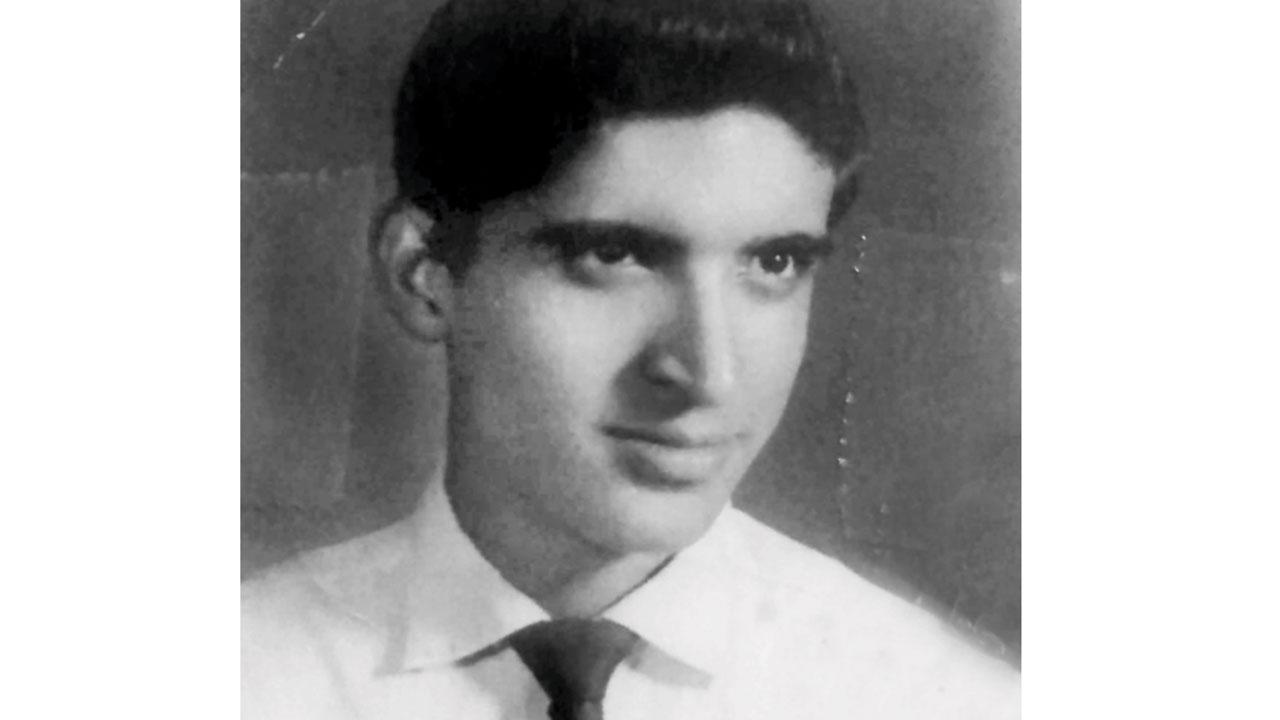

Javed Akhtar at 18 in Bhopal—this picture was taken from an ID card made for the Youth Festival, Delhi, 1963, where young Javed participated in a group discussion. It was at the festival that he happened to meet Amjad Khan who was representing the Bombay University in drama. He moved to Mumbai a year later, in the hope of becoming a director. Akhtar says his early years of struggle in the city made him develop a sense of humour. He is seen here (left) with wife Shabana Azmi during a screening of the play Kaifi Aur Main in 2010. Pic/Getty Images

This entry was posted on October 4, 2009 at 12:14 pm, and is filed under

Akhtar-ul Iman,

Interviews,

Javed Akhtar,

Javed Akhtar father,

Javed Akhtar interview,

Javed Akhtar mother,

Mumbai,

Nasreen Munni Kabir

. Follow any responses to this post through RSS. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Post a Comment