My mother dreamt of becoming an actress and called herself the Beauty Queen of Bengal-Deepti Naval

8:36 AM

Posted by Fenil Seta

Deepti Naval, 18, at her home in Amritsar. Pic Courtesy/A Country Called Childhood: A Memoir, Aleph Book Company

In a just-launched memoir, quintessential girl-next-door Deepti Naval recalls how her mother’s love for dramas and star-struck cousins inspired her to be an actor

MID-DAY (July 3, 2022)

My family loved cinema but if there was one member of the family who actually loved to sing and dance, it was my mother. I have with me old black and white photos that are a visual record of this aspect in my Mama’s life. She was especially fond of doing dramas; she would direct plays, and also act in them along with other young women. I have one distinct memory of a scene being enacted in our house. I’m standing beside the dark blue curtain in the hall kamra and watching Mama rehearse with other women. She is in a saree and her hair is tied in a loose bun. She is wearing high heels and is holding a purse. I recall her entering the room, dangling the batua in her hand. She walks in and there’s some dialogue with the other two women, words that I no longer remember. I watch the scene being performed in front of me with fascination. The door opens and shuts as Mama walks in repeatedly from the thhada entrance, revealing street activity behind her. Light filters in as she stands backlit at the entrance, looking like a veritable star. I wish I could recollect details of the scene being enacted but that’s as far as it goes, my memory of that rehearsal.

Once, some cine stars from Bombay came to our city for a cricket match. Among them were Shyama, Nirupa Roy, and Bhagwan Dada. They performed a show at the Chitra Talkies. That’s the time my mother also performed along with them. When she made her entry on stage, Didi, sitting next to me in the hall started to shout, “Mama! . . . That’s my Mama!” All heads turned to look at us. It was a moment that embarrassed my mother but she’d recall it always with a lot of love. I assume that my mother did some more plays during my baby years, but by the time I was old enough to properly appreciate her talents as an actress she had stopped. Years later, she told me that Bibiji had once said to her, ‘The women at the Women’s Conference say that your daughter-in-law does dramas!’

“After that day,” said Mama, “I stopped. I never did another play. Never uttered a word to my mother-in-law. I just silently gave up everything.”

I was not aware of the impact of that finale in my mother’s life, for she never showed any bitterness. But I know what that sacrifice must have meant to her. This was the woman who dreamt of becoming an actress and called herself the Beauty Queen of Bengal. Today, as I live my life as an artiste, I realize the gravity of those words. “I silently gave up everything...”

It also made me think of Mama’s cousin in Burma, Sunny Bowrie, who had run away from Rangoon to become a dancer in Bombay Talkies. Brian Uncle once told me that Sunny was seen among the group dancers in the song Ramaiya Vasta Vaiya in Raj Kapoor’s film Shree 420. I have since been looking hard at the screen, peering crazily at the dancers in the back rows, looking for Sunny Bowrie, the face in Mama’s box of photographs, to somehow be able to spot him dancing in a movie, a dream that he’d left his home for. But according to Mama, Sunny Bowrie was lost to the family a long time ago.

Besides my mother, others in the family who loved the world of acting, or more properly Hindi movies, were my buas, my father’s sisters. Once a year, my buas would come down from Delhi to Amritsar along with their children. All of us cousins—Manju, Babbu, Indu, Ashu, Alok, Cheenu, Bunny, Didi, and me—would be quite a handful for the elders. In the afternoon, the women would put us kids to sleep and sneak out of the house, to go and see the matinee show at Chitra Talkies.

On hot summer afternoons, all of us kids would lay down for an hour on the terrazzo floor, its touch cool against the skin. The chicks would be drawn in the veranda to keep the sun out as we were all required to take our afternoon nap. That’s when my buas would get up from the floor, one by one, stand before the hat stand mirror, brush their hair, put on various shades of red lipstick, and one by one, slip out of the house. That was their ultimate getting-ready-real-fast trick—comb your hair, apply red lipstick, and off you go!

All the kids knew exactly what was happening, but almost all the time we pretended to be asleep. Occasionally, we’d open our eyes, glance at each other, and suppress giggles.

The biggest influence in my life as an actress perhaps was Indu Bhaiya, my older cousin. Indu Bhaiya, Santosh Bua’s older son, first came to live with us in the year 1958. I was six years old at the time and Bhaiya was probably in eighth class. He had not been doing well in school, so Pitaji suggested that Indu be sent to Amritsar so he could personally supervise his studies. I remember Didi, Indu Bhaiya, and me, playing with white plasticine balls, turning them into pigeons and buffaloes.

The second time that Indu Bhaiya came to Amritsar was in 1962. Bhaiya was by now eighteen, and I was ten. I sported the, then famous, Sadhana Cut, the much in vogue fringe those days, after the look in Love In Simla, and roamed around in my pinafore. Indu Bhaiya would every now and then tease me about looking like Sadhana, the star of those days. This was also the time I was just starting to become self-conscious as a girl. Indu Bhaiya had told his family that he wanted to go to Bombay to become an actor. He would tell us all about Dev Anand; he seemed to be obsessed with the film star.

• • •

Some years down the line, Indu Bhaiya went to Bombay nevertheless and joined films. I was ecstatic—my Bhaiya was so handsome, he looked like Dev Anand, he’ll surely make it. We heard that he’d already got work in a film produced by Rajshri Productions called Dosti. Though Bhaiya was in the supporting cast, for me this was exciting enough.

After his three-year stint in the film industry, and a few more roles, we were told that Bhaiya had given up on Bombay and come back home. When I saw him at Manju Didi’s wedding after his return, I was a bit taken aback. Bhaiya seemed to be in a disturbed state of mind. He later confided in me and told me how he’d fallen in love with an actress in Bombay, but was left heartbroken. He’d lost his mental balance and had briefly undergone treatment as well. Luckily, for him and the family, things would later fall in place for Bhaiya as he put his dream behind, and decided to move on with his life.

But for me, Indu Bhaiya was and has always remained a hero.

Excerpted with permission from A Country Called Childhood: A Memoir by Deepti Naval, published by Aleph Book Company

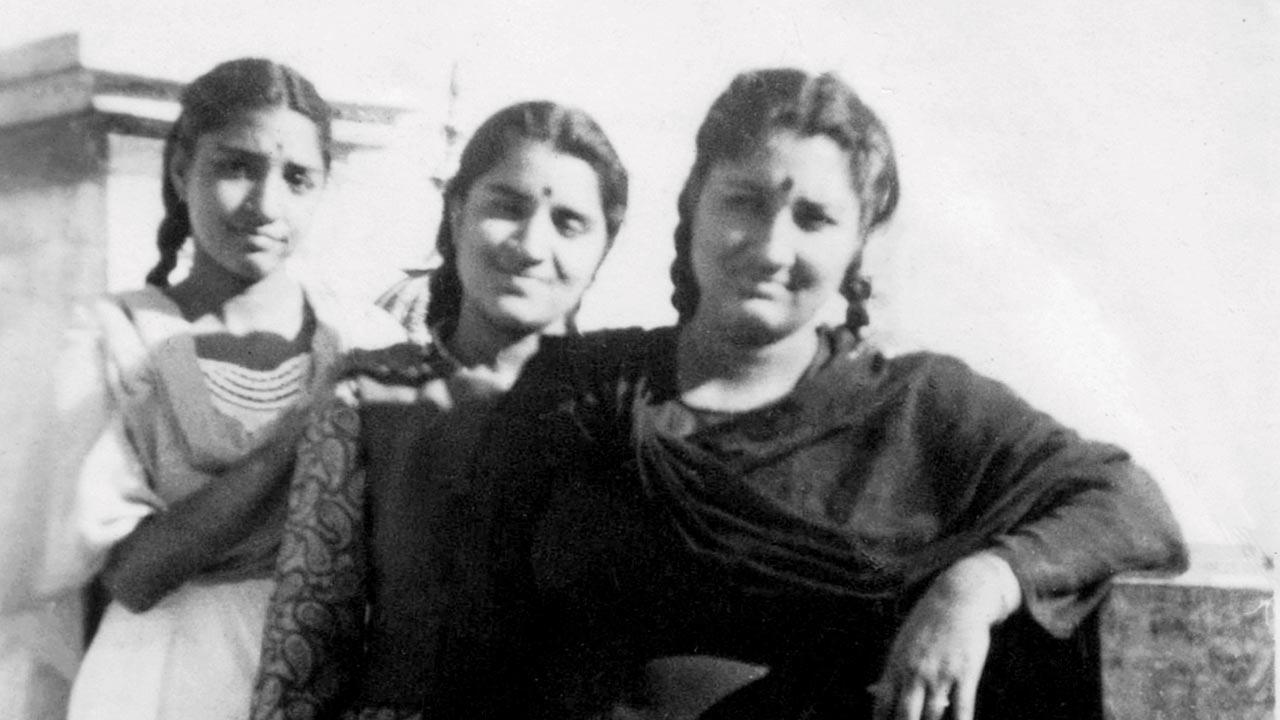

Naval’s buas

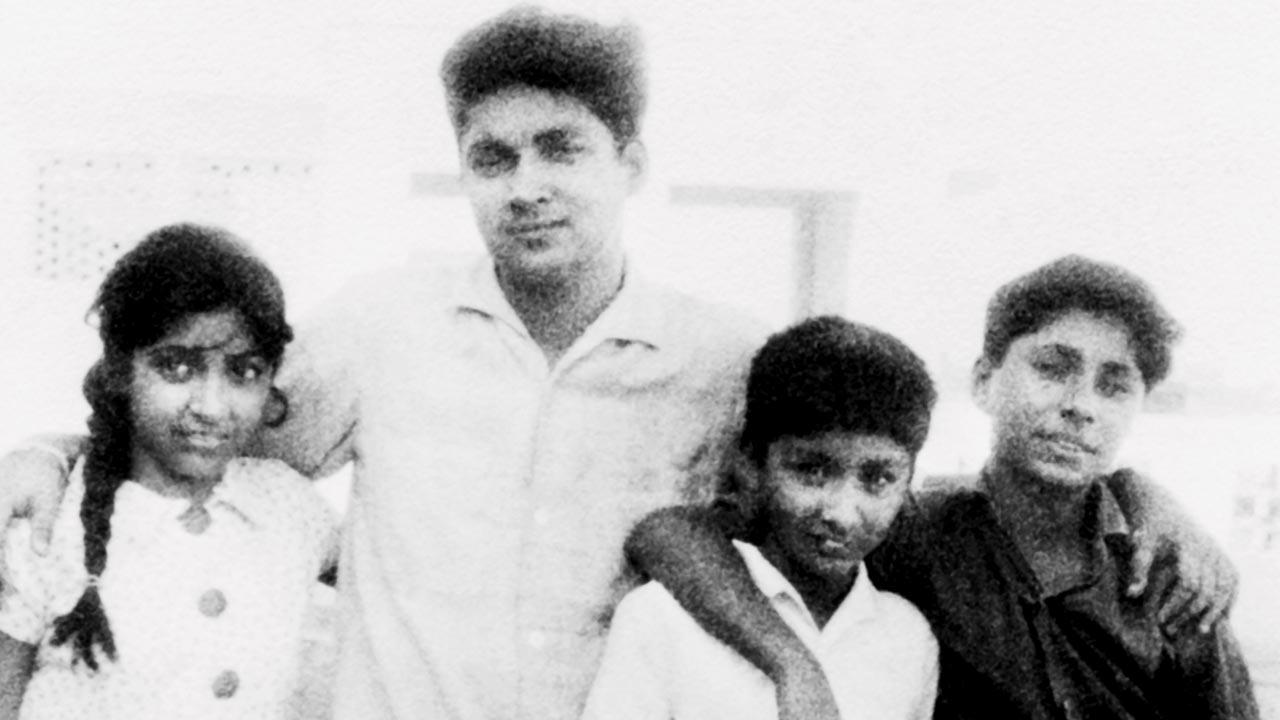

With Indu Bhaiya, Bunny, and Ashu

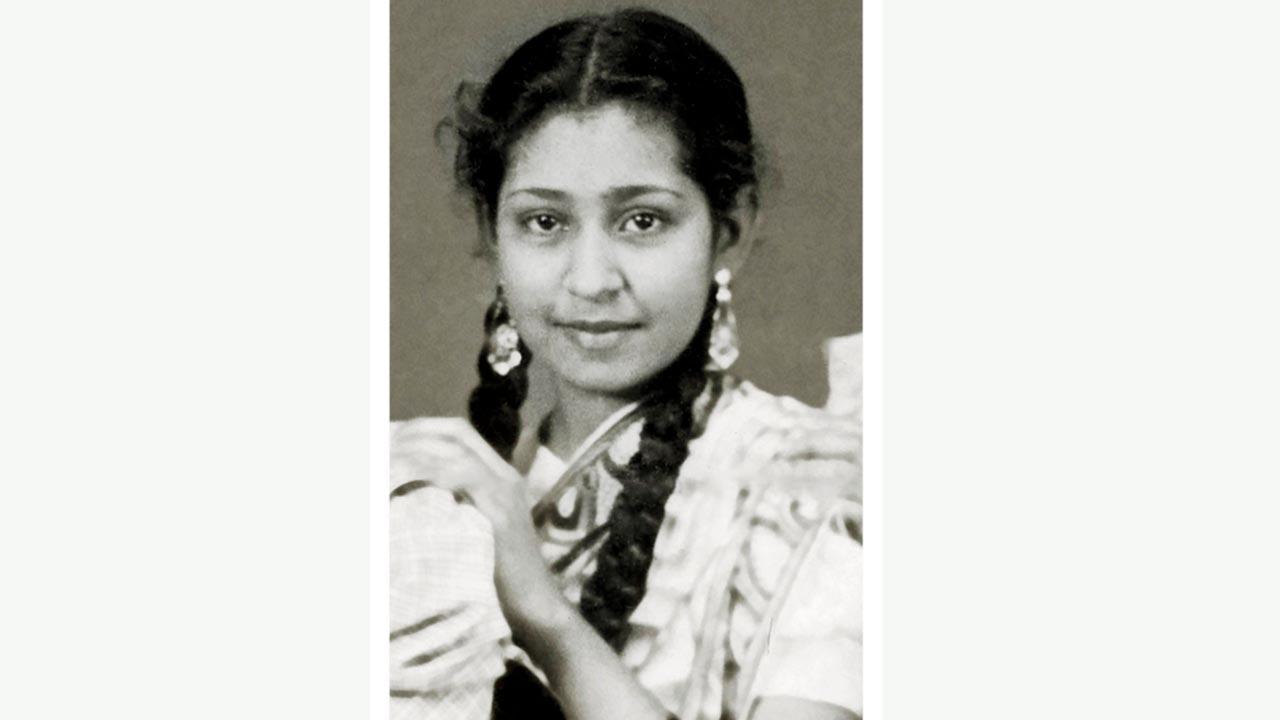

Deepti Naval’s mother Winnie, born Himadri Gangahar. Pics Courtesy/A Country Called Childhood: A Memoir

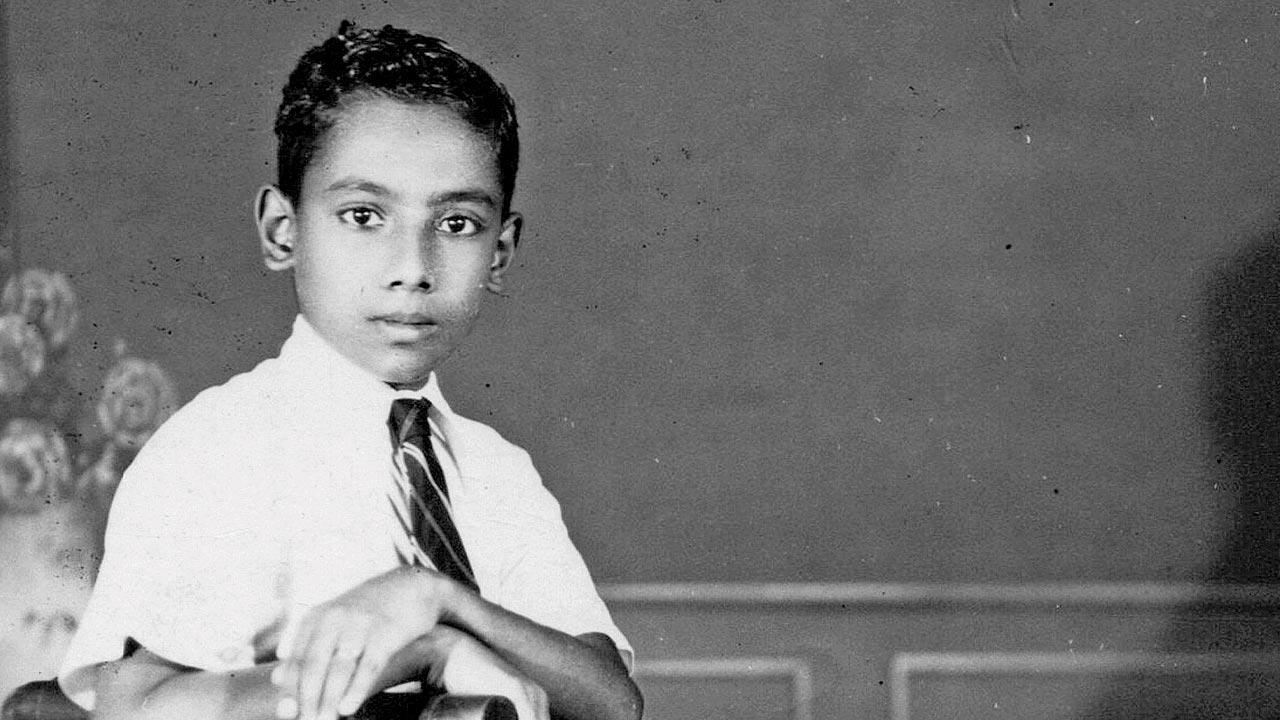

Sunny Bowrie

This entry was posted on October 4, 2009 at 12:14 pm, and is filed under

Amritsar,

Deepti Naval,

Deepti Naval book,

Deepti Naval interview,

Deepti Naval mother,

Dosti,

Interviews,

Shree 420

. Follow any responses to this post through RSS. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Post a Comment