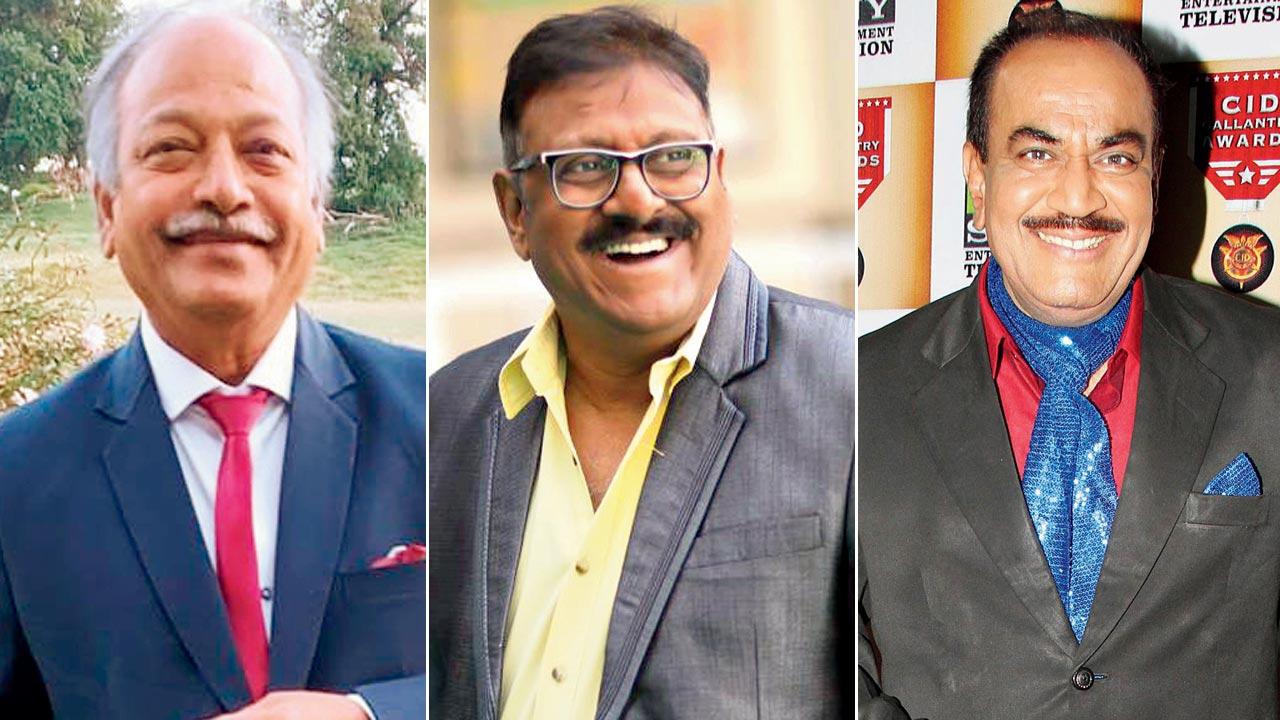

Ashok Saraf began as a banker and so did many other reputed Marathi actors like Vijay Kadam, Vijay Patkar, Shivaji Satam

4:00 PM

Posted by Fenil Seta

Ashok Saraf began as banker, and was honoured with the Maharashtra Bhushan recently. He represents a generation of actors who also balanced passbooks

Gautam S Mengle (MID-DAY; February 4, 2024)

At a Marathi-language comedy show several years ago, veteran actor Ashok Saraf appeared as guest along with fellow actor Sachin Pilgaonkar. The host told Saraf that he was responsible for a bank opening up in his village. How so? “Everyone thinks you have to work in a bank to become Ashok Saraf,” the host quipped, “and that’s all that the youth in my village ever did.”

The 66-year-old veteran was conferred the Maharashtra Bhushan award earlier this week, much to the delight of crores of fans everywhere. And a certain section of actors, too, watched the news with glee—everyone who ostensibly held respectable (albeit homely) jobs in government banks, but slipped out after the teller closed to pursue starry dreams.

For countless aspiring and upcoming actors in the late 80s and early 90s—before banks were corporatised and the system allowed much more latitude—a job at the neighbourhood branch was sought after not just for stability.

“It was like a quota,” says actor Shivaji Satam, who started out at the Central Bank of India in 1973. “Government banks would hire those who excelled at drama competitions, just like sports quota in college or the Railways. And it helped that all of us were fuelled by passion, not minding the dual work, long hours, sudden travel for tours and modest pay.”

Satam shared screen space with Saraf in the 2018 crime thriller, Mi Shivaji Park, and was the face of hit serial CID for years, while appearing frequently in Marathi and Hindi cinema.

“Banks were overflowing with staffers back in the 80s,” says actor Jaywant Wadkar, whom we last saw in Shiv Sena leader Anand Dighe’s biopic Dharmaveer. “There would literally be seven to 10 extra employees in every department, and we had nothing to do. Plus, we were already active in the theatre circuit and our managers knew about our dreams. Unless it was a really busy day, they’d happily allow us to go to rehearsals or shows.”

Wadkar’s story is shared by countless others from his generation, such as Vijay Patkar, Vijay Kadam, Pradeep Patwardhan and Amol Palekar, to name a few. Wadkar tells us that Palekar acted in Rajnigandha and Chhoti Si Baat while being an employee at Bank of India, same as him. Not just men, there was also a slew of female actors as well as some writer and directors who started out as bankers, we learn.

Budding stalwarts, Patkar and Kadam, were Wadkar’s colleagues. All of them had already nourished the acting bug at school and college, more actively in the latter for the benefit of directors would come to recruit fresh talent. “My first play was while in kindergarten,” Kadam, whose last big screen appearance was in Anurag Kashyap’s Kennedy, tells us. “By the time I was in Class V, my teachers had recognized my talent and by the end of college, I directed plays for inter-collegiate festivals. From there to commercial theatre, was but a small step.”

Kadam first broke onto the Hindi film industry with Tiger, an eponymous serial on Door Darshan, centered around a private detective. Kadam played his trusty sidekick, a resourceful man who could procure or facilitate anything; aptly called Genie.

The same held true for Patkar, who acted with Wadkar in the 1988 hit Tezaab. Both starred as members of Anil Kapoor’s merry band of loafers. Patkar is still remembered as Krack to Boman Irani’s Jack for the salted biscuit brand commerials. “The only condition,” he chuckles, “was that we make our bank proud at the annual inter-bank drama competitions. And for exactly this reason, banks were happy to take on as many stage actors as possible. They’d get bragging rights for every successful actor on their roster.”

This was important to the banks as well as the actors. For the actors, it was part of their path to success. The victories at competitions brought small articles in newspapers which directors and producers looked for. It also let them network with other actors and theatre personalities.

Patkar, who joined Bank of India in 1985, concurs that there were too many employees and too little work in banks of the 1980s, unheard of today.

“It really was a golden period for actors,” he says. “Bunking work didn’t have as serious consequences then as now.”

“My manager would even allow me to come to work earlier than others, or stay back later than the rest so that I could make up for the hours taken up by theatre and earn my salary,” Satam recalls.

And despite all the progress and the glamour, this crop of stars never forgot their roots. And this is not just a symbolic statement. Many of them stayed on as employees for years after they became stars.

“Are you kidding me?” Wadkar exclaims when we ask why he didn’t quit after his first big break. “I was the master of reconciliation (the practice of balancing an account statement) in my branch in Fort. When I applied for voluntary retirement in 2000, my manager called me up to ask me if I had lost my mind.”

Did fame affect work? “Yes, but not negatively,” Wadkar laughs, “My branch would enlist me to collect documents from other banks, as they were more willing to oblige me than other employees.”

Wadkar and Patkar both took voluntary retirement in 2000, while Patwardhan served his full tenure of 60 years before retiring in 2020. He passed away a year later after a brief illness.

“Of course, the reliability of the pay cheque mattered, but more than that, we owed the bank our fame and success,” says Patkar loyally.

This dual life wasn’t without its share of problems. There were jealous colleagues and sniggering about some employees “earning dual incomes”.

“It wasn’t unwarranted,” says Kadam, who took voluntary retirement in 1994 to become a full-time actor. “There were so many unauthorized leaves that my bosses called for my records. The running joke was that it took two peons to carry my roster. It was no longer like the olden days when bosses would remind me that it was time to go to rehearsals. I read the room and got out.”

He proudly tells us that 2024 is his 50th year of being an actor.

What lessons did they learn?

“That stage is the best place to start [acting],” says Wadkar promptly. “Nothing shapes you as an actor like theatre. We were luckier than most because we were already acting in school and college before being picked up by commercial theatre directors. They honed our talent into a craft.”

Kadam agrees.

“When I quit my job, I told my family that they don’t need to support me [financially],” the indefatigable 66-year-old tells us. “And I have kept my word. Theatre trained me like nothing else. At times, I’ve walked onto a set for an audition only to be told that the script has changed, and still taken the set by storm at the first take. I still get calls from people who have watched Kennedy at various film festivals since it released last year, even though I haven’t attended a single screening myself.”

As Satam puts it, “We are theatre actors first. The screen just happened to us.”

An entire generation of actors from theatre and cinema started off as bankers in Mumbai. Jaywant Wadkar, who we last saw in the 2022 film Dharmaveer, worked with the Bank of India for 17 years. Pic/Nimesh Dave

Vijay Kadam, Vijay Pakar and Shivaji Satam

In the 1980s, nationalised banks preferred hiring actors who would make them proud at inter-bank drama competitions, like Patkar in this picture

This entry was posted on October 4, 2009 at 12:14 pm, and is filed under

Ashok Saraf,

Bollywood News,

Jaywant Wadkar,

Kennedy,

Shivaji Satam,

Vijay Kadam,

Vijay Patkar

. Follow any responses to this post through RSS. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Post a Comment